(Mike Maharrey, Money Metals News Service) While most market watchers have focused on the wildly yo-yoing stock market over the last few weeks, the Treasury bond market has been flashing warnings.

Higher yields and relatively weak Treasury auctions this week, with a notable drop in foreign buyers, indicate sagging demand for U.S. debt. That’s a big problem for a country that depends on borrowers to finance its massive spending problem.

Writing for the Mises Wire, analyst Artis Shepherd called it “red lights blinking.”

“The bond market is sending a message to the U.S. government that its spending is out of control and the reserve currency ‘privilege’ it has abused for the last 80 years is running out.”

Gold Newsletter publisher Brien Lundin put it another way.

“The rest of the world is selling America.”

The escalating trade war has sped up this yard sale.

When “reciprocal tariffs” went into effect, the bond market initially rallied, and yields fell. (Bond yields and prices are inversely correlated. Strong demand drives up the price and pushes down yields, and vice versa.)

This is exactly what you would expect during a time of uncertainty. U.S. Treasuries have long been valued as a safe-haven asset.

However, the bond rally didn’t last. Treasuries began selling off as stocks recovered when President Trump announced a 90-day tariff pause. But bonds failed to rally again as optimism broke down and the stock market plummeted again.

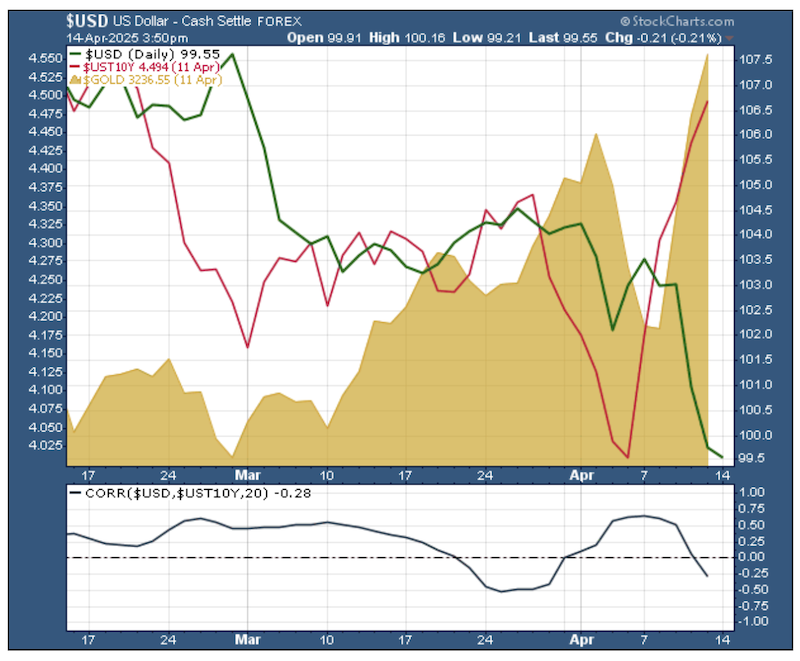

It is highly unusual to see safe-haven Treasuries selling off along with the stock market. We also saw a weakening dollar. Meanwhile, gold rallied to new record highs despite rising bond yields that typically create headwinds for gold.

This was not business as usual during a time of stock market weakness and general market instability. As CNBC noted, “Treasuries and the dollar typically benefit from flight-to-safety environments, a function of the U.S.′ historical financial strength.”

That happened early in the trade war, but it quickly unraveled.

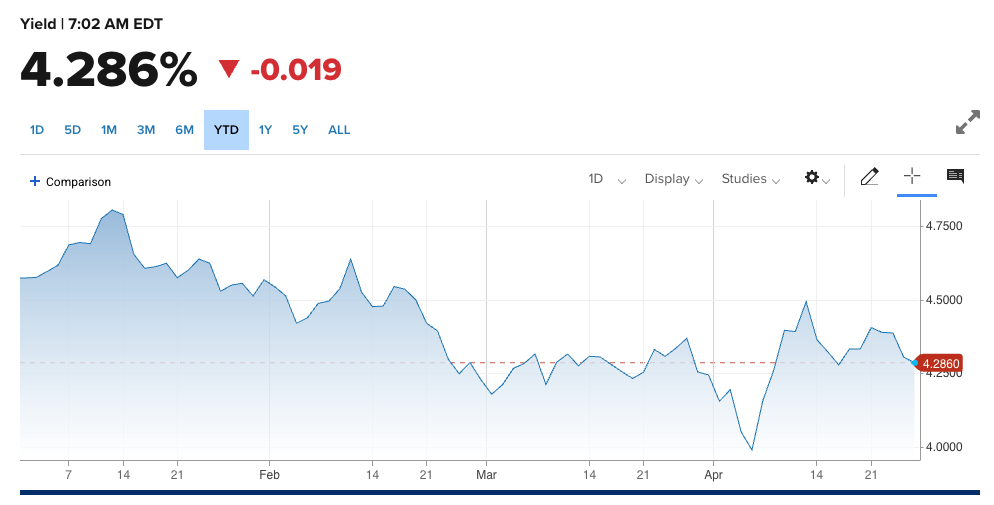

During the week of April 7, the 10-year treasury yield increased by a full half-percent, the biggest weekly rise since 2001. On April 10, the 10-year yield drove above 4.5 percent and closed at 4.49 percent.

The yield has settled in at around 4.3 percent.

This breakdown in the Treasury market during a time of extreme uncertainty and a stock market selloff could signal that investors have lost faith in the U.S. Treasury bond.

Foreign Buyers Snub U.S. Treasuries

Treasury auctions this week are also flashing warning signs with weak demand and a notable drop in foreign investors.

It started with a 7-year bond auction on Tuesday. According to Longport, multiple indicators showed “weak demand, particularly concerns about overseas demand resurfacing.”

The winning yield was 0.2 basis points higher than the pre-issue yield of 4.121, “reflecting a weak demand tail spread, marking the second consecutive occurrence of a tail spread.”

The tail spread is the difference between the highest yield accepted and the “when-issued” (WI) yield right before the auction closes. A large tail signals weak demand, with bidders requiring a higher yield than expected to buy the bonds. This indicates market caution or uncertainty.

“Indirect bidders,” reflecting central bank and foreign demand, came in at 59.3 percent, down from 61.2 percent in March. This implies falling foreign demand for U.S. debt.

The drop in indirect bidders during the 5-year note auction the following day was even more pronounced, falling to 64.04 percent compared to the 6-month average of 70.2 percent.

A 2-year note auction produced similar results. Foreign buyers took 56.2%, the lowest share in two years.

Bloomberg summed it up this way:

“With the U.S. itself now a main source of financial volatility, investors have pushed into other refuges like gold, the Swiss currency and European bonds.”

BNY Markets analyst John Velis told Bloomberg, there is an “ongoing retreat by cross-border real money investors” from U.S. bond markets, including the Treasury market.

So What?

What does this notable decline in foreign buyers and sagging demand for Treasuries more generally mean?

Well, it’s a big problem for Uncle Sam.

This problem was already evident before the tariff chaos. Bond yields spiked late last year even as the Fed was cutting rates. While the central bank dropped interest rates by 100 basis points, long-term Treasury yields spiked up by over 100 basis points.

At the time, WolfStreet noted, “There are rising concerns in the bond market about the ballooning U.S. debt, and about the flood of new supply of Treasury securities that the government will have to sell in order to fund the out-of-whack deficits. Treasury buyers and holders are spread far and wide, but higher yields may be necessary to reel in the mass of new buyers needed, even as the Fed is shedding its Treasury holdings through QT.”

This situation has further deteriorated since the trade war went hot. As Shepherd explained, “The recent tariff pronouncements accentuated a trend that began some time ago—notwithstanding the Federal Reserve’s persistent attempts to hide it by printing money and purchasing treasuries—the skepticism of American credit in light of its profligate spending and utter lack of will to change course.”

In other words, in Shepherd’s view, this isn’t just about tariffs.

“The root cause of this decline is the inflationary nature of U.S. fiat money combined with an unchecked fiscal profligacy, the result of which is an American empire that is effectively bankrupt.”

How long it will be before the Fed capitulates and begins buying U.S. bonds to artificially increase demand and drive yields lower through quantitative easing is anybody’s guess, but Shepherd thinks this is the likely endgame.

“A rational response to recent events would be for the U.S. government to cut spending, return to a semblance of sound money, and—more generally—begin to scale back the level of its involvement in the lives of everyday Americans. That’s about as likely as the fox guarding the henhouse. More probably—guided by the dominant and ignorant Keynesian model—a new cycle of quantitative easing will arise, forcefully but temporarily driving interest rates down until inflation comes back even stronger. If it continues on this path, the U.S. will dig itself deeper into this hole until it’s buried in it.”

Mike Maharrey is a journalist and market analyst for Money Metals with over a decade of experience in precious metals. He holds a BS in accounting from the University of Kentucky and a BA in journalism from the University of South Florida.