(Mike Maharrey, Money Metals News Service) Producer prices rose significantly more than expected in July, throwing markets into turmoil and calling into question what seemed like an almost certain Federal Reserve interest rate cut in September.

The big jump in wholesale price inflation seemed to confirm worries that aggressive tariffs would eventually manifest in higher price inflation. However, a deeper look at the numbers reveals that import taxes can’t be the sole source of this price spike.

July PPI By the Numbers

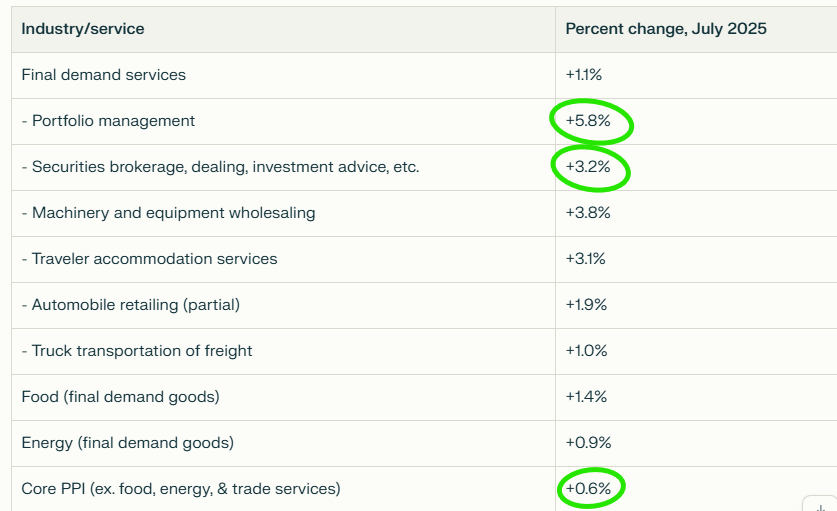

The producer price index for final demand surged 0.9 percent month-on-month in July, according to Bureau of Labor Statistics data. It was the biggest monthly increase in producer prices since June 2022.

Wall Street forecast a 0.2 percent increase in PPI.

On an annual basis, producer prices are up 3.3 percent. It was the biggest 12-month increase since February.

Stripping out food and energy prices, core PPI also charted a 0.9 percent gain. That was against a 0.3 percent forecast.

Producer prices reflect costs incurred by businesses at various stages in the production process. The PPI is considered a leading inflation indicator as companies will ultimately pass at least some of those increased costs to consumers.

The Consumer Price Index (CPI) has also shown some heating up of price inflation, but nothing on the scale of the July PPI.

Was This the Manifestation of Tariffs in the Economy?

Mainstream media immediately blamed tariffs for the big jump in producer prices. High Frequency Economics chief economist Carl Weinberg told Reuters the report was “a kick in the teeth for anyone who thought that tariffs would not impact domestic prices in the United States economy,” adding that it was “strong validation” of the Fed’s wait-and-see approach to monetary policy.

While there was some sign of price inflation in goods, Final Demand for Services exploded by 1.1 percent month-on-month in July. Annualized, core service prices jumped by 4 percent.

Rising service prices are not a product of import tariffs.

A big rise in the cost of financial services drove the services PMI higher. Portfolio management fees soared 5.8 percent, reflecting the surging stock market.

Hotel and motel room prices, airline fares, and freight costs also surged higher.

The price of goods wasn’t immune from this inflationary pressure, gaining 0.7 percent in June. This may well reflect the costs of tariffs. For instance, food prices were pushed upward by a jump in the price of fruits and vegetables.

Excluding food and energy, goods prices rose a more modest 0.4 percent, with notable increases in the cost of steel, aluminum, and primary nonferrous metals.

While the mainstream has taken the July PPI data as a confirmation of accelerating tariff-related price inflation, the fact that services are leading the way undercuts this narrative because services are not subject to import taxes.

WolfStreet noted, “It’s services inflation at the consumer level that is so hard for the Fed to contain, which is why the Fed fears services inflation so much.”

Two-thirds of U.S. consumer spending is on services.

Core service consumer prices are also heating up. They came in at 4.4 percent annualized, the worst reading in six months. This accounts for 60 percent of the total CPI.

So Why Is Price Inflation Heating Up?

But if tariffs aren’t causing the surge in service prices, what is?

Good old-fashioned monetary inflation is the most likely culprit.

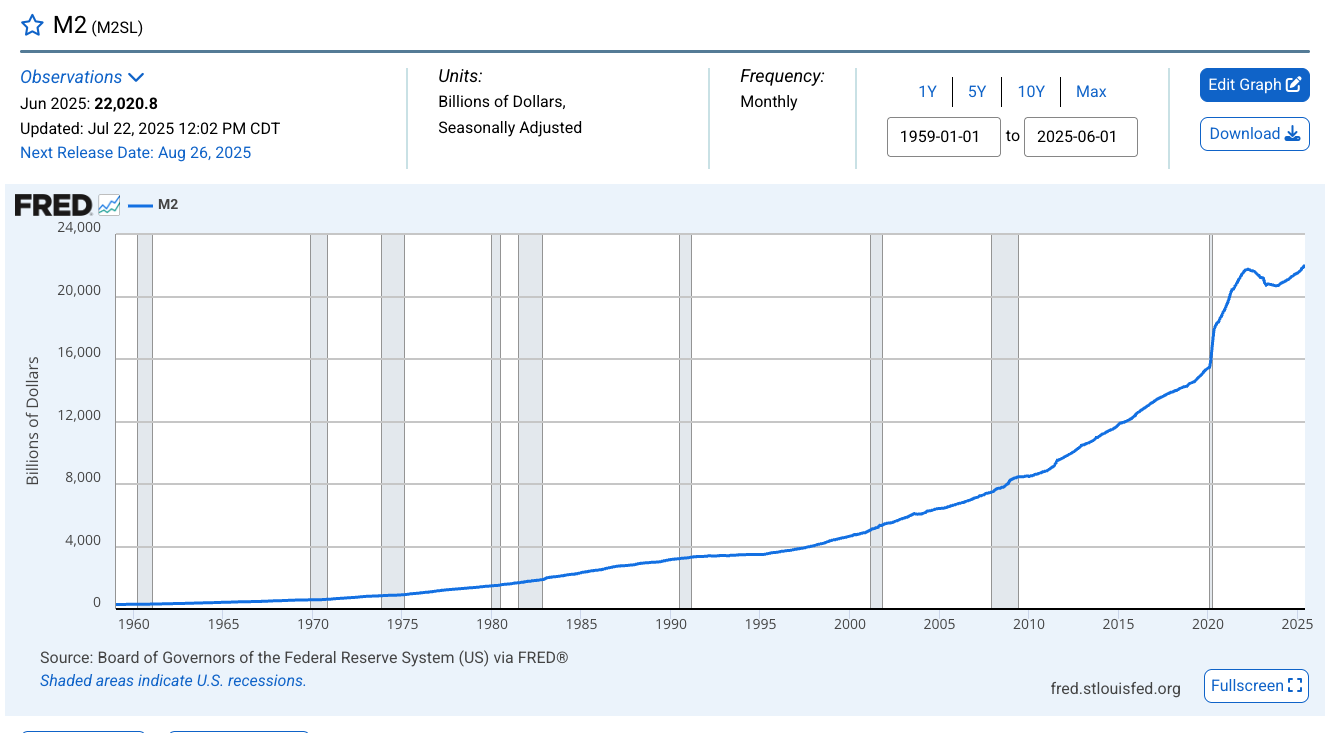

I have argued for months that the Federal Reserve never did enough to slay inflation. Given the amount of money pumped into the economy between the Great Recession and the pandemic (nearly $9 trillion), coupled with more than a decade of artificially low interest rates, raising rates to 5.5 percent and shedding a relatively small amount from the bloated central bank balance sheet was enough to paper over some of the symptoms, but not strike the root of the problem.

Since then, the Fed has cut rates by a full percentage and it has slowed down its balance sheet reduction scheme. Meanwhile, the money supply has been expanding for well over a year. As of the end of June, the money supply had grown by more than $600 billion since its low point in mid-2023. As of the end of that month, the M2 money supply stood at $22 trillion, above the peak reached during the pandemic.

This, by definition, is inflation. It shouldn’t come as a shock that this monetary inflation is starting to bleed into producer and consumer prices.

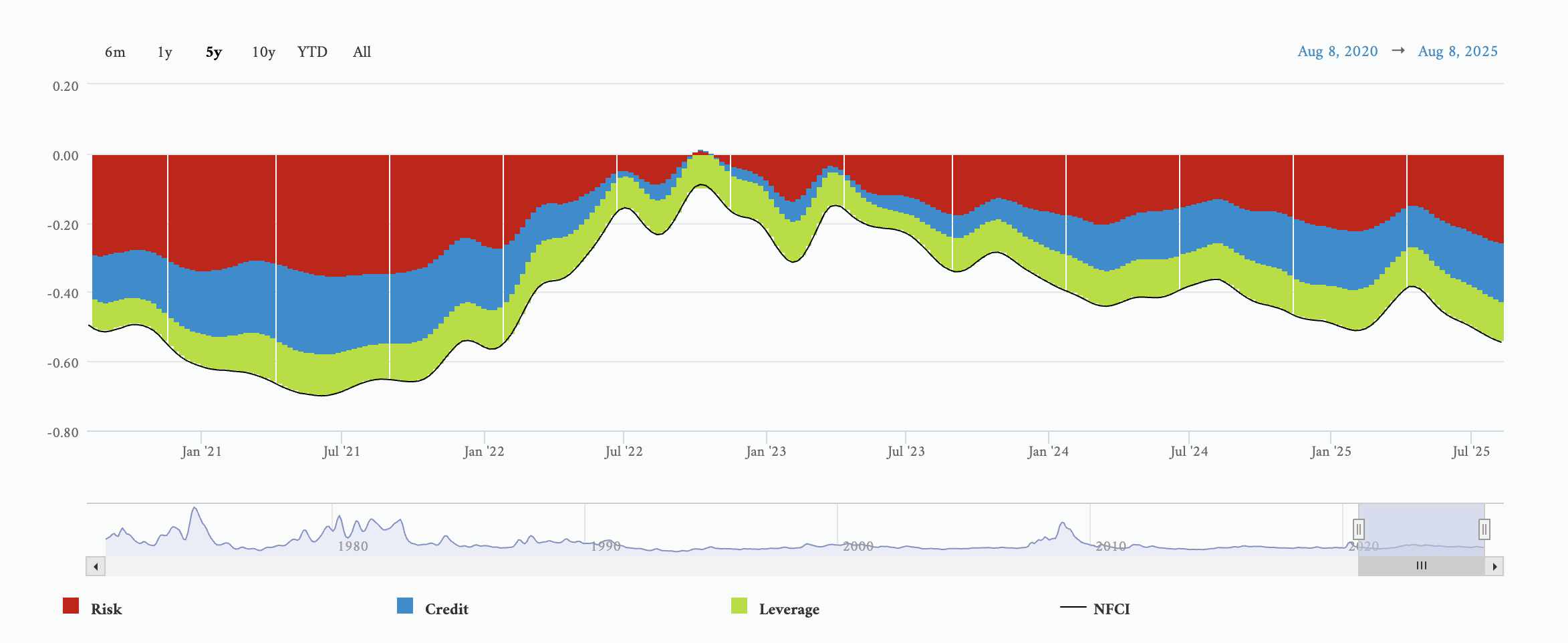

The Chicago Federal Reserve’s own National Financial Conditions Index also indicates that monetary policy is loose from a historical perspective. In fact, conditions weren’t even tight at the peak of the tightening cycle.

Understanding Inflation

It’s important to understand that tariffs don’t cause generalized price inflation. They can cause certain prices to rise, but import taxes don’t drive up the general price level throughout the entire economy. All things being equal, other prices will drop as some prices rise on tariffed products and consumers adjust their behavior.

There is only one thing that causes price levels to generally rise throughout the economy, and that is an increase in the supply of money and credit. As economist Milton Friedman put it, “Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon.”

The fact that we now define rising prices as inflation creates a great deal of confusion. It wasn’t always that way. Inflation used to be precisely defined as an increase in the supply of money and credit. One of the impacts of monetary inflation is price inflation.

Henry Hazlitt is best known for his brilliant book Economics in One Lesson. In another essay titled “Inflation in One Page,” he explained why using a more precise definition of inflation is crucial.

“Inflation is an increase in the quantity of money and credit. Its chief consequence is soaring prices.

“Therefore inflation—if we misuse the term to mean the rising prices themselves—is caused solely by printing more money. For this, the government’s monetary policies are entirely responsible.” (Emphasis added)

Tariffs make a good inflation scapegoat, but never forget what Hazlitt said. “The government’s monetary policies are entirely responsible.”

The political class would prefer you not grasp this reality because money creation is the lifeblood of big government. That means they’ll blame everything in the world for inflation, so you don’t point your fingers at the real culprits – all of them!

Mike Maharrey is a journalist and market analyst for Money Metals with over a decade of experience in precious metals. He holds a BS in accounting from the University of Kentucky and a BA in journalism from the University of South Florida.