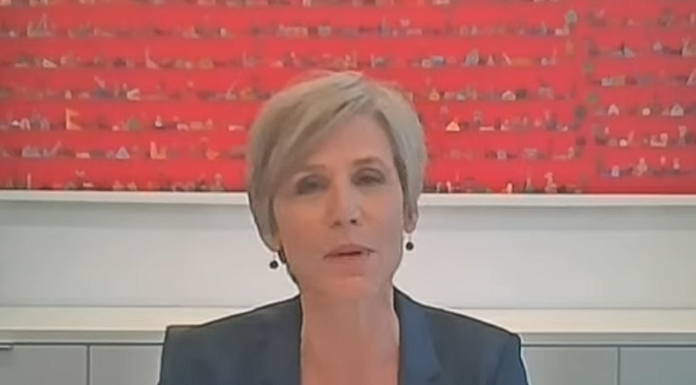

During testimony before the Senate Judiciary Committee, Obama era Deputy Attorney General Sally Yates threw former FBI Director James Comey under the bus, admitting that he had gone “rogue” in his investigation of the Trump campaign’s alleged ties to Russia.

Those ties—raised largely by the debunked Steele Dossier, which was commissioned by the Hillary Clinton campaign—formed the basis of the two-year Mueller investigation, which ultimately determined that Trump officials had not colluded with Russia.

However, the fallout of the FBI’s corrupt probe resulted in several dubiously predicated indictments based on process crimes such as perjury that the FBI claimed were committed in the course of its counterintelligence probe into the fake claims.

During a grilling with Sen. Lindsey Graham, R-SC, the chairman of the Judiciary Committee, Yates admitted that she disapproved of the FBI’s use of the Logan Act to set a perjury trap for incoming national security adviser Michael Flynn.

“Did Comey go rogue,” asked Graham.

“You could use that term, yes” Yates replied.

With Attorney General Loretta Lynch already facing scrutiny amid allegations of her own election interference in a parallel case involving Hillary Clinton’s mishandling of classified emails, she was relegated largely to the sidelines of the of the anti-Trump “Crossfire Hurricane” probe.

Yates was the signatory on one of the FBI’s original FISA applications, seeking permission to spy on Trump advisers under the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act.

She also was present at a Jan. 5, 2017 meeting in the Oval Office, during which President Barack Obama discussed with Comey and others the possibility of weaponizing the Logan Act against the incoming administration.

Also confirmed to have been present in the meeting were then-Vice President Joe Biden and then-national security adviser Susan Rice.

Recently declassified notes from disgraced former FBI agent Peter Strzok indicate that he was also present or had firsthand knowledge of the meeting.

The basis of the meeting was to discuss intercepted communications between Flynn and Russian diplomat Sergey Kislyak over the newly elected Trump administration’s policy on Russian sanctions.

Despite having known of Russian interference during the election, Obama had only decided after the fact, with a month until Trump was due to take power, that he would expel Russian diplomats and heighten tensions due to their apparent efforts to use social media disinformation to sway the election.

However, it is unclear that the Kremlin sought specifically to benefit Trump rather than to sow chaos, as reports have suggested it may also have provided the sourcing of the Steele Dossier.

Nonetheless, Flynn sought to reassure Kislyak—who had maintained close ties to the Obama administration while making repeated overtures to the new administration—that the Russians should not escalate Obama’s provocation before the transfer of power.

During the meeting, Yates claimed she was shocked to discover that Obama had been briefed on the intercepts of Flynn’s December conversations with Kislyak even though she was unaware of them.

It has since been revealed that top White House and intelligence officials accessed a deeply classified intelligence report and unmasked Flynn’s identity dozens of times between the November 2016 election and the January 2017 inauguration.

Contradicting Strzok’s notes, Yates denied during her testimony Wednesday that it was Biden who proposed using the antiquated Logan Act against Flynn.

“I don’t remember the vice president saying much of anything in this meeting,” Flynn said of the Jan. 5 gathering. “… I have a vague memory of Director Comey mentioning the Logan Act.”

Yates said, however, that she couldn’t recall if that had been during the meeting or afterward.

The Jan. 5 Oval Office meeting—which also was the subject of national security adviser Susan Rice’s notorious Inauguration Day CYA memo—was significant in the fact that FBI agents investigating Flynn had proposed dropping the probe the day before.

However, due to administrative errors, they had not filed the paperwork—much to the relief of the “7th floor” where Comey and other top FBI officials worked at the agency headquarters, according to declassified Strzok disclosures.

Yates claimed that the agents had recommended closing the Flynn case before knowing about the intercepts of phone calls with Kislyak, but according to Strzok’s notes, Comey admitted in the Oval Office meeting that the substance of the phone calls was legitimate.

Yates downplayed the significance of the Logan Act in the probe, insisting that the FBI was interested in a counterintelligence operation, not a criminal one.

“The whole prism here —that this was all about the Logan Act—is [false],” she told Graham.

“You can certainly talk to foreign leaders,” she continued. However, this was about Flynn “undercutting the sanctions,” she said.

Graham seemed incredulous that the administration would feel the need to take such actions with only two weeks remaining before Trump—and Flynn—took office.

“That is stunning as hell… you can’t really talk to anybody, you can’t hit the ground running,” he said.