(Mike Maharrey, Money Metals News Service) As the Federal Reserve revs up the money-creating machine even higher, the money supply is already growing at the fastest rate since July 2022, in the early stages of the tightening cycle.

This is inflation, by definition.

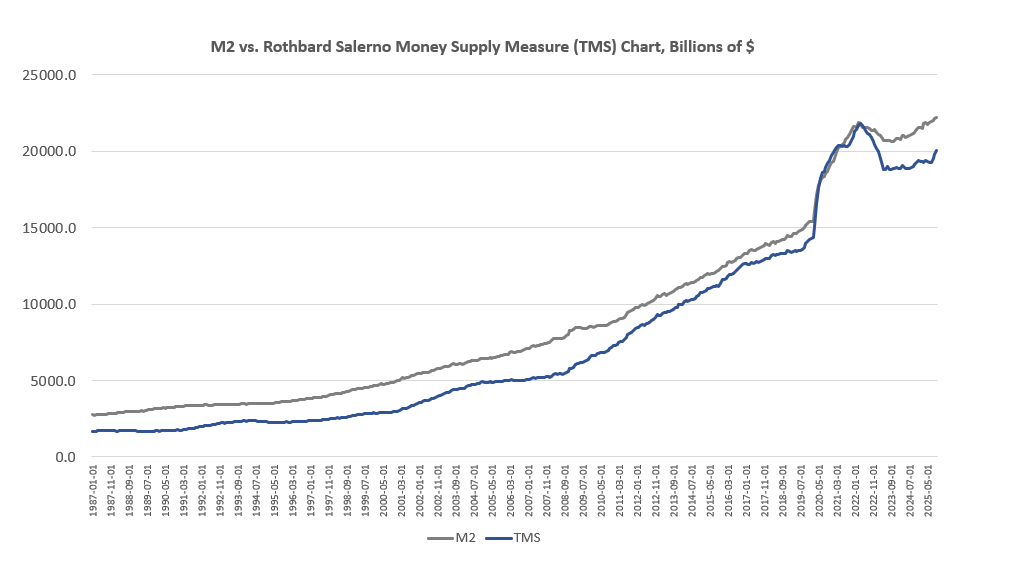

After peaking in April 2022, the money supply began to decline as the Fed hiked rates that year. The money supply bottomed in October 2023 and began increasing again. The money supply is now well above the pandemic peak.

And money creation has accelerated over the last several months.

Based on the “true,” or Rothbard-Salerno, money supply measure (TMS), the money supply grew at 4.76 percent year-on-year. That was up from the September increase of 4.06 percent. Money supply growth was also up significantly compared to October of last year, when year-over-year growth was 1.27 percent.

August, September, and October all posted some of the largest month-on-month growth rates we’ve seen since 2022, rising 1.18 percent, 1.4 percent, and 1.14 percent, respectively.

Economists Murray Rothbard and Joseph Salerno developed the TMS metric to provide a more accurate measure of money supply fluctuations.

Money supply growth as measured by the Fed’s M2 metric is surging even faster. Year-over-year, it grew by 4.63 percent in October, up from 4.47 percent in September.

M2 is now at the highest level it’s ever been, at nearly $22.3 trillion. TMS hasn’t returned to its 2022 peak but is running at a 34-month high.

Looking at the bigger picture, the central bank has expanded the money supply at an exponential rate since the 2008 financial crisis.

Based on the TMS metric, the money supply has grown by over 200 percent since 2009. Looking at it another way, more than 2/3 of the current money supply has been created since the financial crisis.

That’s a lot of money creation – i.e., inflation – in a short period of time!

The Money Printer Is Humming Again

The fact that money supply growth has ramped up since the Fed began cutting interest rates underscores an important point. The central bank doesn’t have to create money through quantitative easing to increase the money supply. Artificially low rates are inflationary in a fractional reserve banking system.

And at the December meeting, the Federal Reserve announced a pivot back to money printing with a return to QE operations beginning this week.

According to Fed officials, the central bank will purchase $40 million in Treasury Bills on Friday (Bills are short-term Treasuries that mature in one year or less). From that point, purchases will “remain elevated for a few months” before they are “significantly reduced.”

Of course, you will not hear any central banker or mainstream pundit utter the words “quantitative easing.”

In fact, if pushed, they’ll almost certainly deny that they’re doing it. They’ll call it “reserve management,” or tell you they’re engaged in “technical operations” to keep the financial system’s plumbing moving.

However, an expansion of reserves is an expansion of reserves, whether you call it quantitative easing or not.

In practice, the Fed plans to start buying Treasury bills with money created out of thin air. This will increase the money supply and put downward pressure on Treasury rates. The balance sheet will grow; liquidity will increase; risk asset bubbles will get more air. This is exactly what QE does. So, call it what you want. The effect is the same as QE.

It creates inflation.

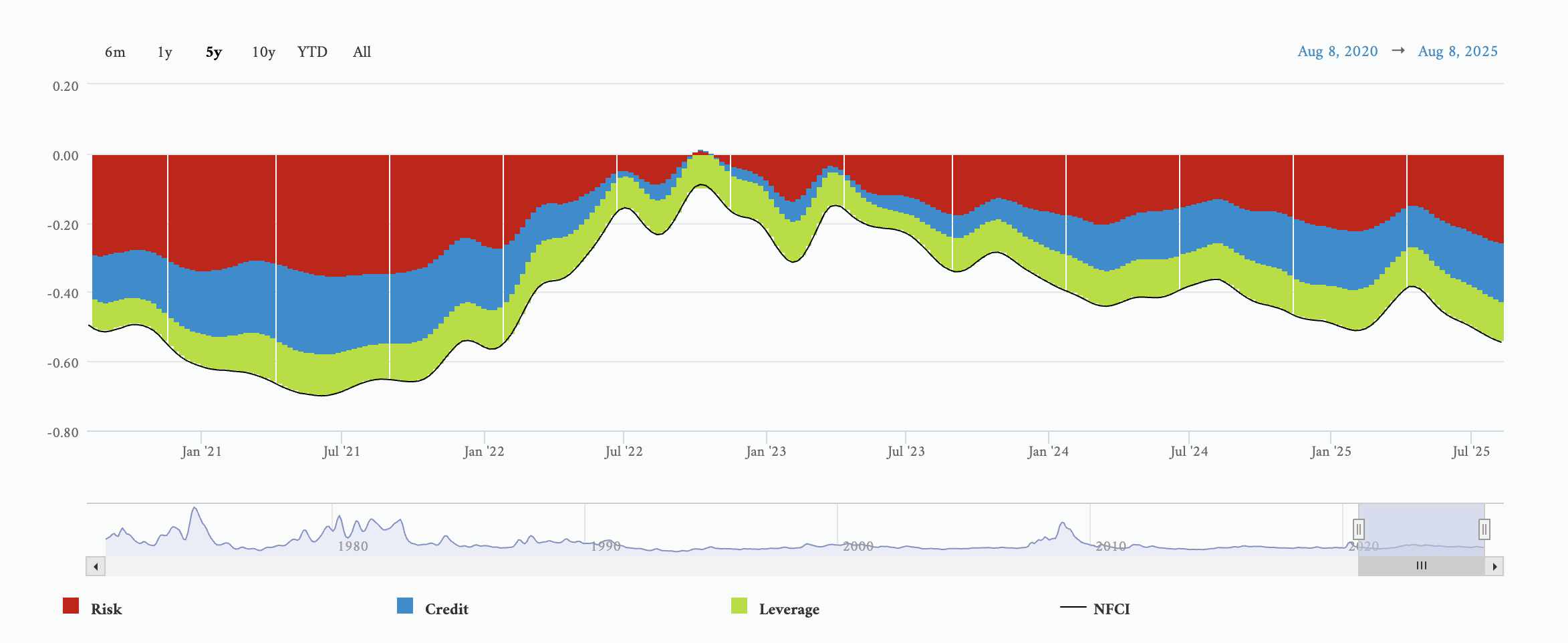

Fed chairman Jerome Powell claims that monetary policy is close to neutral, but it is clearly loose. In fact, based on the Chicago Fed National Financial Conditions Index, monetary policy has been historically loose throughout the tightening cycle in 2022/2023.

This Is Inflation

While inflation watchers focus almost exclusively on price measures such as the CPI, an expanding money supply drives price inflation. In fact, inflation used to be defined as an increase in the amount of money and credit in the economy, or more succinctly, an expansion in the money supply.

Economist Ludwig von Mises defined it this way in his essay “Inflation: An Unworkable Fiscal Policy“:

“Inflation, as this term was always used everywhere and especially in this country, means increasing the quantity of money and bank notes in circulation and the quantity of bank deposits subject to check.”

Henry Hazlitt is best known for his brilliant book Economics in One Lesson. In another essay titled “Inflation in One Page,” he explained why using a more precise definition of inflation is crucial.

“Inflation is an increase in the quantity of money and credit. Its chief consequence is soaring prices.

“Therefore inflation—if we misuse the term to mean the rising prices themselves—is caused solely by printing more money. For this the government’s monetary policies are entirely responsible. (Emphasis added)”

This confusion of terms is precisely why so many people believe inflation is a thing of the past. They are only looking at one symptom of inflation (rising prices), completely ignoring the inflation pumping into the system as you read this.

Here’s the rub: those calling for even lower rates aren’t necessarily wrong. The U.S. economy is addicted to easy money. It is loaded up with debt and simply can’t function in a normal interest rate environment over the long term. Higher interest rates don’t play well with the massive Debt Black Hole.

A higher interest rate environment will eventually crack the debt-riddled economy and pop the bubbles. The economy needs its easy money drug.

As I’ve been saying for months, the Federal Reserve is in a Catch-22. It simultaneously needs to cut rates to prop up the easy money-addicted economy and hold rates steady (or even raise them) to keep inflation at bay.

That’s not going to happen. Even as the central bankers at the Fed try to talk down the likelihood of further interest rate cuts, they are actively loosening monetary policy at every meeting. That means that no matter what Powell & Company say, you need to brace yourself for more inflation.

Mike Maharrey is a journalist and market analyst for Money Metals with over a decade of experience in precious metals. He holds a BS in accounting from the University of Kentucky and a BA in journalism from the University of South Florida.