(Mike Maharrey, Money Metals News Service) In another sign that we are entering an era of even looser monetary policy, Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell hinted that balance sheet reduction is about to come to an end.

“Our long-stated plan is to stop balance sheet runoff when reserves are somewhat above the level we judge consistent with ample reserve conditions. We may approach that point in coming months, and we are closely monitoring a wide range of indicators to inform this decision.”

In practice, this means the central bank will stop reducing its holdings of Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities, maintaining the size of its balance sheet at the current level.

Balance sheet reduction, or quantitative tightening (QT), pulls liquidity out of the financial system by reducing bank reserves and shifting government debt financing to the private sector. This tightens funding conditions and market debt. It is effectively deflationary.

Powell said, “Some signs have begun to emerge that liquidity conditions are gradually tightening,” thereby necessitating the end of QT.

More significantly, an end balance sheet reduction would take some pressure off the Treasury market, as the central bank would have to purchase new bonds as the old ones mature. In effect, this would create additional artificial demand in the Treasury market.

Powell didn’t provide a timeline for ending balance sheet runoff.

The Fed chair also hinted that more interest rate cuts are in the cards. He also alluded to the tightrope the central bank is trying to walk.

“If we move too quickly, then we may leave the inflation job unfinished and have to come back later and finish it. If we move too slowly, there may be unnecessary losses, painful losses, in the employment market. So, we’re in the difficult situation of balancing those two things.”

Fed Balance Sheet Operations Explained

Quantitative Easing

Interest rate policy gets the most attention, but the Federal Reserve balance sheet is an important monetary policy tool. In effect, it serves as a direct pipeline to the money supply.

When the Fed buys assets – primarily U.S. Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities – it does so with money created out of thin air. Those assets go on the balance sheet, and the new money gets injected into the financial system and ultimately the broader economy.

This process is known as quantitative easing (QE).

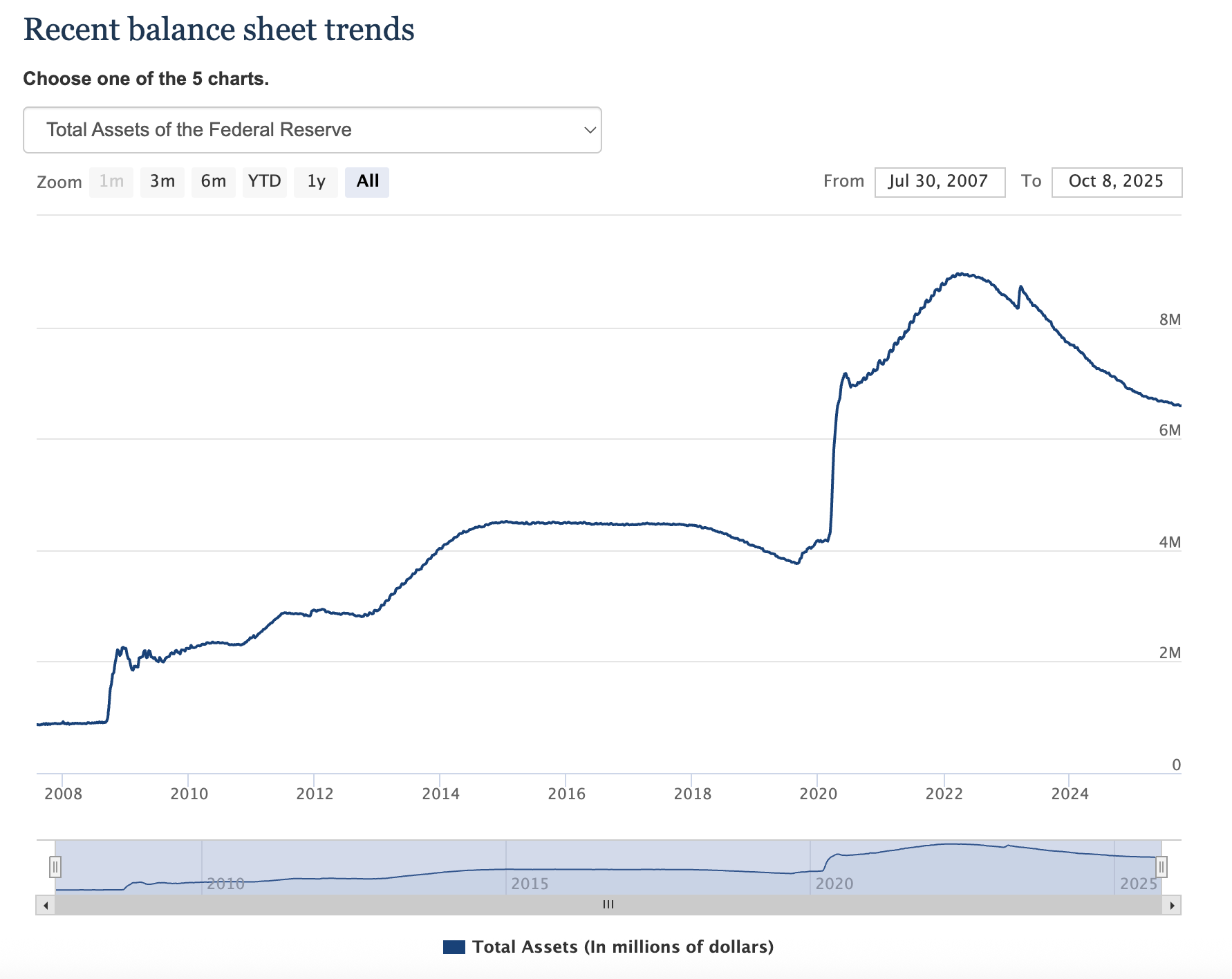

Before the 2008 financial crisis and Great Recession, the balance sheet was just over $900 billion. By the end of the pandemic era, it stood at just under $9 trillion.

In other words, the Fed pumped over $8 trillion into the economy in 14 years through QE.

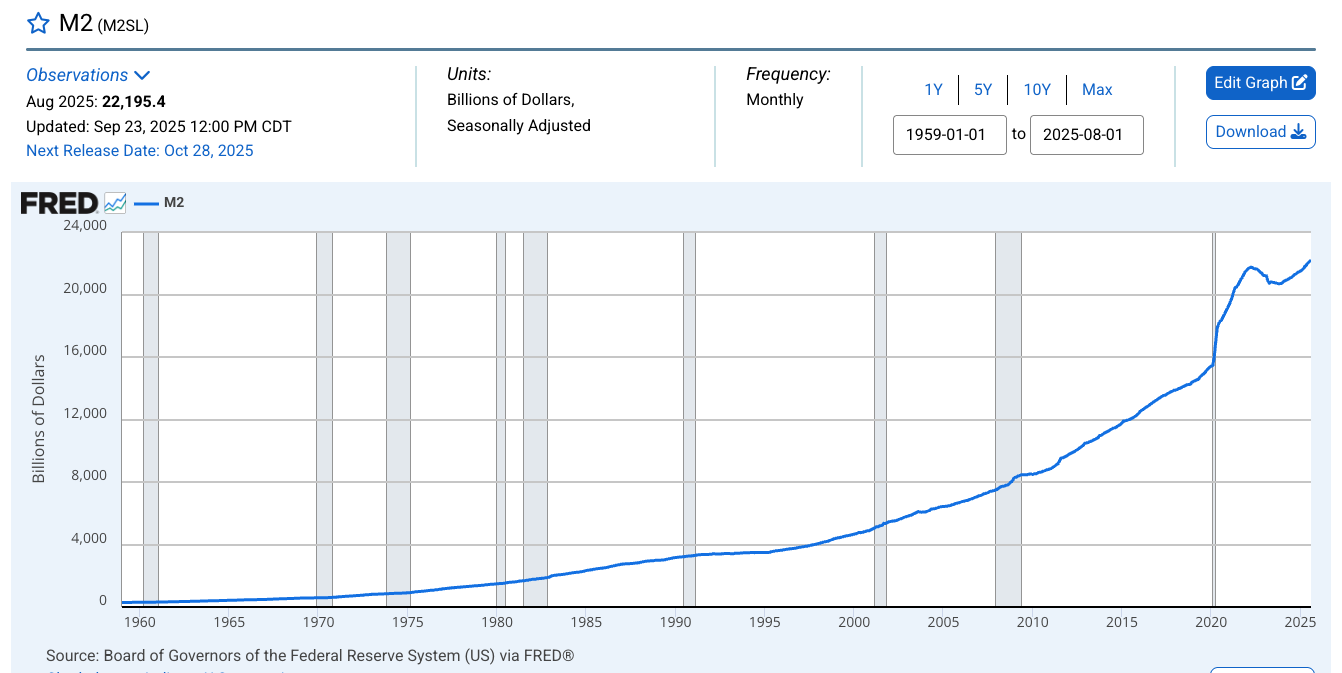

We can see the impact of QE in the trajectory of the money supply. Note that it declined after the Fed began QT and cut interest rates in 2022, but it has since resumed its relentless climb.

When Ben Bernanke launched the first round of QE at the onset of the Great Recession, he assured Congress that the Fed was not monetizing the debt. (When the Fed buys a bond with money created out of thin air, it is effectively turning that debt into money — thus the term “debt monetization.”) He said the difference between debt monetization and the Fed’s policy was that the central bank was not providing a permanent source of financing. He said the Treasuries would only remain on the Fed’s balance sheet temporarily. He assured Congress that once the crisis was over, the Federal Reserve would sell the bonds it bought during the emergency.

When Ben Bernanke launched the first round of QE at the onset of the Great Recession, he assured Congress that the Fed was not monetizing the debt. (When the Fed buys a bond with money created out of thin air, it is effectively turning that debt into money — thus the term “debt monetization.”) He said the difference between debt monetization and the Fed’s policy was that the central bank was not providing a permanent source of financing. He said the Treasuries would only remain on the Fed’s balance sheet temporarily. He assured Congress that once the crisis was over, the Federal Reserve would sell the bonds it bought during the emergency.

That never happened.

And then the Fed doubled down, expanding the balance sheet by nearly $5 trillion during the pandemic.

This is, by definition, inflation.

As former Federal Reserve Governor Kevin Warsh explained in an op-ed published by the Wall Street Journal last year, there is a direct connection between this monetary expansion and price inflation.

“The monetary base is up 60 percent since the pandemic. Another measure of money, M2, is up 36 percent in the past four years. The inflation surge in the same period– cumulatively about 22 percent– shouldn’t have been a surprise.”

Quantitative Tightening

Quantitative tightening unwinds quantitative easing.

As Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities mature, the central bank doesn’t replace them, thereby shrinking the size of the balance sheet over time.

Since the Fed isn’t replacing the bonds, the U.S. Treasury must raise money from the public to redeem the central bank. Of course, Uncle Sam is broke. That means the Treasury Department has to sell a new bond on the open market – essentially borrowing money to pay off the old debt. When a private individual or entity buys a Treasury, they typically use cash, reducing their bank deposit. In effect, this lowers overall financial system reserves and shifts more debt financing to the public.

The Fed announced a balance sheet reduction plan in March 2022 when it could no longer convince everybody that price inflation was “transitory.” The plan wasn’t exactly ambitious, given the amount of inflation it created during the pandemic. If the Fed followed the blueprint (and it didn’t), it would take 7.8 years for the Fed to shrink its balance sheet back to pre-pandemic levels. This doesn’t even account for the trillions added in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis.

And of course, the central bank didn’t stick with the plan. The Fed slowed the pace of balance sheet reduction in May 2024.

From its peak, the Fed has run around $2.4 trillion off the balance sheet. That sounds impressive, but it only represents about half of the increase during the pandemic alone.

Powell said that the Fed has no plans to reduce the balance sheet back to pre-pandemic levels.

So much for Bernanke’s promise.

Why End QT Now?

If expanding the money supply is inflationary, it logically follows that to truly beat down price inflation, the Fed needed to shrink the balance sheet substantially. Theoretically, it should have reduced the size of the balance sheet at least to the neighborhood of pre-crisis levels, as Bernanke promised.

Rate hikes aren’t enough to ring all the liquidity out of the economy. Warsh made this very point in his op-ed, explaining that if the Fed is serious about taming inflation, it needs to significantly reduce the size of the balance sheet. In other words, it needs to undo the money creation of the past decade-plus.

I didn’t.

And it won’t.

So, if inflation isn’t at the 2 percent target, why did the Fed start winding down its balance sheet reduction in June? And why are they talking about ending it altogether today?

Probably because they learned their lesson in 2018.

After the 2008 financial crisis, the Fed maintained its bloated balance sheet until 2017. When it finally made an effort to reduce the balance sheet, it didn’t last very long.

Why?

Because the monetary tightening was about to break the economy and the financial system.

The stock market crashed in the fall of 2018, and there were recession warning signs flashing in the economy. The Fed put rate hikes on hold in December that year and started cutting rates in 2019. In August 2019, the Fed reversed course on balance sheet reduction and launched a new round of quantitative easing as the short-term lending markets went haywire. Fed officials refused to call it QE. They even denied that it was QE. But whatever you want to call it, the result was the same as QE. The balance sheet began to expand again.

The Fed was able to shrink the balance sheet more this time around because the monetary expansion was bigger and faster during the pandemic than it was in 2008. But the central bankers know they’re playing with fire. They know that this economy can’t run without easy money. And that’s exactly why they’ve already slowed their roll even though they continue to claim inflation isn’t dead yet.

The National Debt Problem

While Powell & Company would never admit it, the central bank has no choice but to end balance sheet reduction due to the federal government’s borrowing and spending problem. When Bernanke claimed the central bank wasn’t monetarizing the debt, he was either hopelessly naive or he was lying.

In effect, the Fed supports the government’s borrowing by creating artificial demand for Treasuries. This drives the price higher and yields lower, driving the U.S. government’s borrowing costs down.

If the Fed weren’t holding so much U.S. debt, Treasury interest rates would be substantially higher.

An end to QT makes sense given that the federal government is paying more than $1 trillion in interest expense right now.

While an end to balance sheet reduction won’t inject newly created money into the economy, it will reduce the number of bonds the government has to sell on the open market, thereby easing supply, raising Treasury prices, and putting downward pressure on yields.

Simply ending balance sheet reduction might not be enough. Given falling global demand for Treasuries and persistently high yields, the central bank may well have to launch quantitative easing again in the near future to press its thumb harder on the Treasury market. In effect, this would be a return to money printing.

Mike Maharrey is a journalist and market analyst for Money Metals with over a decade of experience in precious metals. He holds a BS in accounting from the University of Kentucky and a BA in journalism from the University of South Florida.