(Affordability and charging access remain the biggest obstacles to consumer acceptance of electric vehicles and the government’s ambitious transition targets.

These factors pose even greater challenges for a demographic that has been seemingly overlooked by policymakers—those residing in multiunit dwellings.

“The transition to EVs in the United States will hit a deep pothole unless the more than one-third of the 124 million households that rent can be convinced to purchase an EV,” said longtime systems engineer Robert Charette in a recent article he authored for IEEE Spectrum.

“More importantly,” he said, “a compelling case must be made to tens of thousands of condo community associations as well as the millions of rental property owners that they should install EV chargers.”

The issue becomes more complex when viewed from the diverse perspectives of renters, condominium owners and landlords.

Landlords question the rationale behind covering the costs, while tenants who may only stay for several years are hesitant to pay for installations. Condo owners face the additional hurdle of homeowner association board approvals.

Charette told the Center Square the confluence of affordability, the number of renters and the age of apartment buildings all affect the options available.

Within apartment buildings, Charette said, there is a striation of socioeconomic capability and “a high percentage of people can’t afford to pay their rent right now.”

The question is how many renters in a building would make it worthwhile for landlords to invest in chargers, even with government subsidies?

The answer only invites more questions.

The average price of a new EV is just over $55,300—something Charette says is scarcely affordable for the average family.

He cited recent reports stating that millions of Americans—especially low-income households—struggle with unaffordable rent increases due to inflation and housing shortages. Despite decreasing prices of used EVs, the majority are still beyond the budgets of most renters.

Research indicates homeowners purchase EVs at nearly six times the rate of renters. The discrepancy, he explained, is primarily because most EV owners can charge at home using Level 2 chargers.

Renters of single-family and mobile homes with dedicated parking spots can charge at home using Level 1 chargers without requiring added electrical upgrades or landlord permission. However, many of the roughly 28 million people living in apartment buildings, Charette said, lack on-site EV charging.

Illinois is the latest state to pass a “right to charge” law requiring parking spots at new homes and multiunit dwellings to have conduit installed to accommodate chargers. California, Colorado, Florida, Hawaii, Maryland, New Jersey, New York, Oregon and Virginia have passed similar legislation.

The details vary by state, but in many cases the tenant is typically responsible for the cost of the equipment, installation, maintenance and electricity used, as well as liability insurance. In addition, many leases state that any improvements made to the property by the tenant belong to the owner after their agreement expires.

Given the expense and the fact that, on average, renters stay for only a few years before moving, Charette suggests the number of tenants installing chargers is likely to be extremely small.

Many renters in suburban areas lack access to robust mass transit, and therefore rely on cars more often than their city counterparts.

Lehigh Valley engineer James Daley, a member of the IEEE Standards Association, told the Center Square the migration of households to the suburbs has provided incentives to build apartment complexes where convenient parking is a major amenity.

Daley said having several apartment buildings in a single suburban complex is typical—and parking requirements, such as the number of parking spaces allocated for each dwelling unit, are usually covered in land-development ordinances.

Even if a building’s wiring can accommodate EV charging loads, the problem, he saids, is the way electric service is provided to the buildings.

Electricity is distributed from the utility company to a transformer and then to the service panel containing meters for each household. The significance of this, Daley said, is that it is not possible to dedicate an EV charger to a specific household.

He questioned how installing a percentage of parking spots with charging units could be accomplished equitably. Additionally, who pays for the installation? Is the cost spread over all households? Are those without EVs subsidizing the cost of charging?

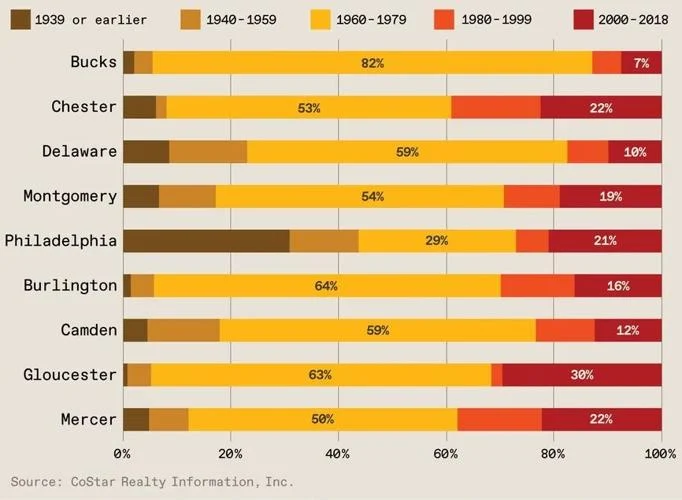

Charette said the age of apartment buildings in the U.S. is an overlooked factor and addressing the issue would necessitate infrastructure upgrades.

This raises more questions, one being: if a landlord bears the cost, will it lead to rent increases?

For instance, data he obtained from a Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission report showed a large percentage of apartment buildings in the greater Philadelphia region were more than 40-years-old and were typically occupied by low-income and minority renters.

IEEE Spectrum and the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission / GRAPHIC: via The Center Square

Something else Charette said hadn’t been thoroughly considered was the risk involved when charging in multilevel underground parking garages—and, in some locations, the uppermost level may be designated solely for charging.

If there were an EV fire at the lower levels without rapid detection and suppression capabilities, he said, “It’s like having a toxic chemical explosive going off in your basement.”

While cities develop programs to facilitate on-street charging, and other innovations are being explored, alternatives to at-home charging include the use of public charging stations or charging at the workplace, if available.

“What exists today is a vicious cycle” Charettes said, where renters, even if they can afford it, are reluctant to buy EVs due to a lack of reliable, convenient, and affordable charging, and owners of rental properties—especially of apartment buildings—will not invest in EV chargers because too few tenants use them.