(Mike Maharrey, Money Metals Exchange) There were more corporate bankruptcies in 2023 than there were during the pandemic of 2020.

Higher interest rates and massive levels of corporate debt drove the flurry of business failures last year.

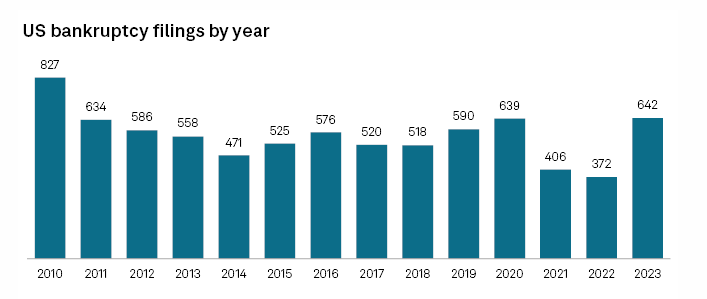

There were 642 corporate bankruptcy filings in the U.S. in 2023, according to S&P Global Market Intelligence. That was a 72.6 percent increase over the 2022 total and the largest number of bankruptcy filings since 2010.

The biggest bankruptcy of 2023 happened in December when Pennsylvania Real Estate Investment Trust filed for protection. The company had more than $1 billion in liabilities.

Other big companies that filed for bankruptcy in 2023 included WeWork, Rite Aid, Yellow, and Akumin.

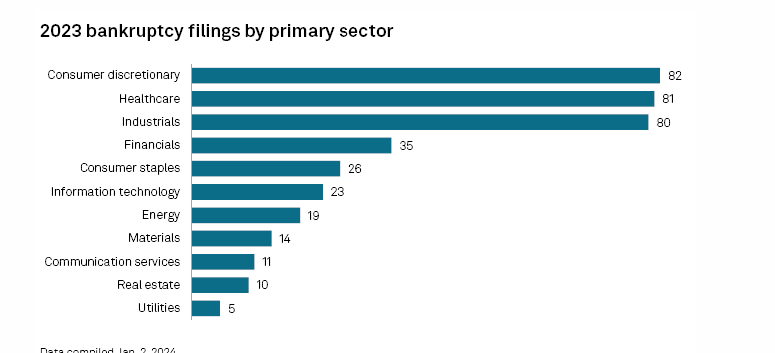

Consumer discretionary companies charted the most bankruptcy filings by sector with 82 filings. These are companies that sell non-essential goods and services including fast food, furniture, and travel services.

The healthcare and industrial sectors also recorded a large number of bankruptcy filings.

During the year, 95 California companies sought bankruptcy protection. There were 75 filings from Texas and 68 from Florida. New York added 58 bankruptcies last year, with New Jersey registering 31.

Corporate bankruptcies were part of a broader trend in the U.S. According to data from Epiq AACER, personal bankruptcy filings rose 18 percent to 419,559 in 2023.

Epiq AACER VP Michael Hunter said he doesn’t think the number of bankruptcy filings will slow in the coming year.

We expect the increase in number of consumer and commercial filers seeking bankruptcy protection to continue in 2024 given the runoff of pandemic stimulus, increased cost of funds, higher interest rates, rising delinquency rates, and near historic levels of household debt.

BLAME THE FED

What caused the big surge in bankruptcies in 2023?

You can blame the Federal Reserve.

Simply put, the U.S. economy cannot function long-term in a high interest rate environment. Easy money is gone and companies are struggling to survive without that mother’s milk.

The central bank drove interest rates from zero to 5.5 percent in a relatively short period of time to fight price inflation. But the real problems started long before the rate hiking cycle.

In the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, the Fed pushed dropped interest rates to zero and held them there for nearly a decade. It didn’t start trying to normalize rates in earnest until 2017, and it failed miserably. In the fall of 2018, the economy started getting wobbly and the stock market crashed. The Fed paused rate hikes in December 2018 and cut rates three times the following year. The pandemic gave the central bank the excuse it needed to slash rates back to zero in 2020.

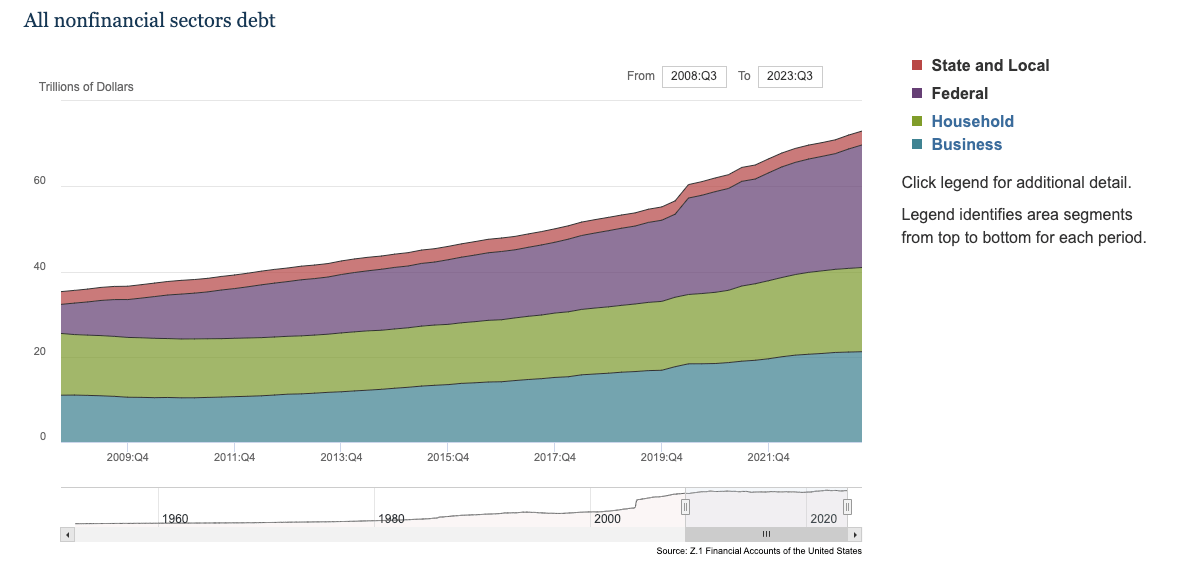

Other central banks followed the Fed’s lead. More than a decade of easy money had a predictable effect. Corporations, governments, and individuals ran up mountains of debt.

And why not?

Money was cheap, and policymakers gave the impression that the easy money gravy train would never end. The Federal Reserve and the U.S. government incentivized borrowing, so people borrowed. After all, incentives matter.

But when it became clear that price inflation wasn’t transitory, the Fed was forced to act. Now we’re in an untenable environment with debt bubbles as far as the eye can see straining under the pressure of higher interest rates.

This is precisely why the Fed started talking about rate cuts in 2024 even though price inflation is nowhere near the 2 percent target. Everybody knows that this debt-distorted economy can’t run with higher interest rates. It will inevitably break things in the economy.

The rise in bankruptcies last year was just one of many symptoms. There was also the banking crisis last spring that the Fed managed to paper over with a bailout program.

The S&P Global report notes that the surge of bankruptcies will likely continue into 2024.

Although investors expect the Federal Reserve to cut interest rates as early as March, companies will still have to contend with relatively high interest rates and robust wage growth in the near term.

The Fed is between a proverbial rock and a hard place. It can ease interest rates down, risking a resurgence of price inflation, or it can hold its ground and risk crashing the economy.

Both scenarios seem less than ideal.