Headline USA interviewed investigative reporter Arthur Bloom and a former Trump White House official about the failed attempt to achieve clemency for Donald Reynolds Jr., a prison inmate with possible connections to the Obama-era Fast and Furious scandal. This is their story.

(Ken Silva, Headline USA) “A black NRA member sitting in a prison for terrorists may be the missing link in Fast and Furious.”

This is the evocative subtitle introducing a Nov. 24, 2020, article in the American Conservative about Donald Reynolds Jr., a black businessman serving life plus 75 years on drug, weapon and money-laundering charges.

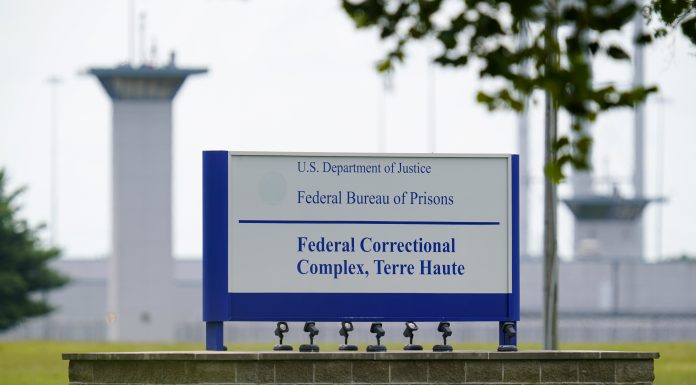

The result of an exhaustive investigation from reporter Arthur Bloom, the article raises questions about why Reynolds, a nonviolent offender with no prior convictions, is sitting in one of the country’s two maximum-security “Communication Management Units”— prison facilities designed to prevent terrorists and organized crime figures from communicating with their networks outside.

Reynolds claims that the U.S. government retaliated against him for refusing to be a government informant in a Fast and Furious-like operation. His connections to Fast and Furious are, as Bloom says, murky and complex, and are more fully detailed in articles by Bloom and Reynolds’s fellow inmate, Marty Gottesfeld.

But in a nutshell, Bloom has shown numerous dubious aspects to the Department of Justice’s case, which sought to portray Reynolds as a drug- and gun-running kingpin.

For starters, Reynolds was a legal gun owner. He possessed Class 3 stamps required to own machine guns, “meaning he would have been closely tracked by the ATF,” Bloom notes.

After raiding Reynolds’s home and his parents’ home in 2008, law enforcement found nothing illegal. The scant evidence presented by the U.S. government included a wrapper with cocaine residue supposedly plucked out of his trash by an IRS agent, and two cash-counting machines. Other “evidence” presented by prosecutors included the fact that law enforcement found drugs in a storage unit owned by the same company that had also rented a separate unit to Reynolds—a tenuous connection at best, says Bloom.

Then, there’s the criminal background of government’s star witness against Reynolds: Joshua Correa, a cartel boss who’s admitted to ordering a hit on U.S. soil and moving more than 1,000 kilograms of cocaine to cities all over the country. Prosecutors said Correa moved drugs from Mexico’s “Placido Benitez cartel”—a group that Bloom could find no record of outside this case—to Reynolds in Knoxville.

Couple these anomalies with the fact that Reynolds was doing business with an array of shady characters in Arizona around the same time as Operation Fast and Furious, and top it off with the fact that then-Attorney General Eric Holder, who oversaw Fast and Furious, attended some of his pretrial hearings—Bloom says there’s enough evidence to lend credence to Reynolds’s claim that government retaliated against him for refusing to be an informant.

Bloom laid all this out and more in his November 2020 article, hoping that it would rekindle interest in the Obama-era Fast and Furious scandal, as well as help the Reynolds family’s effort to obtain a pardon from President Donald Trump in the final days of his administration.

But amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, election controversy and the overall social unrest of 2020, Bloom’s article received little attention, and had no impact.

It was around that time that Bloom decided to get personally involved. Reynolds’s family had been having difficulties submitting his clemency petition—they received bizarre email bounce-backs when trying to send the application—and so Bloom decided to submit the application himself.

Bloom told Headline USA that he realizes his decision to become personally involved transgresses journalistic boundaries, but he did it because he believed Reynolds deserves clemency, and because the family needed his help.

“I didn’t really know what else to do. I gave them the means of getting in touch, and it didn’t work,” he said. “I don’t know why.”

What happened next isn’t clear.

Bloom frequently checked on the status of the application in the chaotic final days of the Trump administration, but received little information. “I did speak to one of AG Bill Barr’s deputies about the case, though it was in a non-reportorial capacity so I’m not able to divulge who or what was said,” he said.

Trump left office on Jan. 20, 2021, and Bloom never heard what happened with the Reynolds petition.

A former Trump White House official with knowledge of the issue said he doesn’t think the application was seriously considered.

“I never recall any discussion among anyone talking about his petition, ever,” said the former official, who spoke to Headline USA under the condition of anonymity.

The official explained that clemency petitions often fall under one of two categories: They’re either submitted formally through the DOJ’s Office of the Pardon Attorney, or they’re made in an ad hoc fashion through supporters of the President.

“You can go to a campaign event and tell a staffer, ‘Hey will you hand this letter to the President: It’s a clemency application,’” the official said.

The official said the first category of petitions is more likely to garner serious attention—which was one factor working against Reynolds. Further complicating Reynolds’s case was the fact that clemency pardons are usually granted to someone who admits their guilt.

“Traditionally, factors for clemency include how long you’ve served your time, have you shown remorse, are you no longer a danger or a threat to others, have you improved yourself in prison. Those don’t factor in questions about innocence. Saying, ‘Hey, it was all a setup … [clemency] then becomes a quasi ‘innocence project,’” the former White House official said.

“That’s not really something the executive branch is suited for.”

Regardless of why Reynolds’s clemency petition was unsuccessful, Bloom was dejected from the process. After investigating this case and a slew of other controversial issues, he decided to largely drop out of conservative media and confine his writing to his Substack.

Little to no public attention was given to Reynolds after Bloom’s work, until CIA whistleblower John Kiriakou wrote about him in a Substack article last month. In that article, Kiriakou said he intends to write about the Reynolds case, and that he was told by multiple people that Bloom was warned by “DOJ” to “walk away” from the story.

Not so, says Bloom—though he has dropped off the map due to “strange things” happening to him in recent years.

“A lot of strange things have happened to me over the past few years, but after you’ve worked on five or six stories that have a chance of provoking retaliation—Hunter Biden, Google blacklisting, Don Reynolds, January 6—it’s hard to know who or what is putting pressure on you,” Bloom wrote on his Substack recently.

“Is it possible I was sort of frozen out because of all of this?”

Bloom declined to elaborate on some of those “strange things” that happened to him, but told Headline USA he’s happy Kiriakou has taken up the Reynolds cause.

Bloom admits the Reynolds case has an uphill battle to garner political support—the Left is turned off by the guns, and the Right is turned off by the alleged drugs—but he said he hopes conservatives give it more attention.

“You hear conservatives talk about pulling yourself up by your bootstraps. This is what the Reynolds family did. And what was done to his family is unacceptable,” Bloom said, refering to the fact that the government has seized much of the family’s assets via civil forfeiture.

“His dad was a contractor at Oak Ridge National Lab. He served in the Army. This is a good family. This is a guy who’s getting young black Knoxvillians out of the ghetto. You can’t sandbag people like that.

“This has to be answered for.”

Ken Silva is a staff writer at Headline USA. Follow him at twitter.com/jd_cashless.