(Mike Maharrey, Money Metals News Service) Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell and other Fed officials have started signaling interest rate cuts are coming, but it’s almost certainly too late to rescue a debt-ridden bubble economy addicted to easy money.

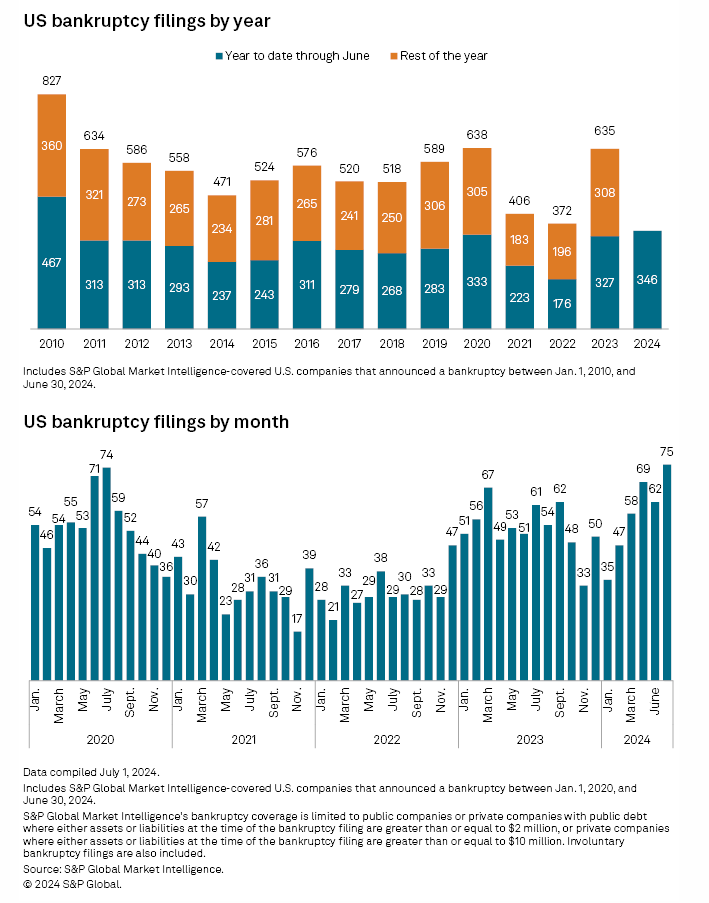

We’re already seeing the impacts of tighter monetary policy rippling through the economy with corporate bankruptcies through the first half of 2024 at the highest level in over a decade. That includes during the pandemic era in 2020 and 2021.

S&P Global called the surge of bankruptcies in June “historic” noting that it was the highest number recorded in a single month since at least the beginning of 2020.

According to S&P Global data, 75 corporations filed for bankruptcy in June alone. That drove the number of filings through the first six months of 2024 to 346, “higher than any comparable figure in the prior 13 years.”

The last time we saw bankruptcy filings at this level through the first half of a year was in 2010 in the wake of the Great Recession.

In 2023, there were 642 bankruptcy filings, also the highest number since 2010.

What is causing corporations to go bankrupt?

The first factor S&P Global mentioned was “higher interest rates,” along with supply chain issues and slowing consumer spending.

It is likely the slowdown in consumer spending is also due to higher interest rates.

As price inflation gripped the economy after the pandemic stimulus spree, Americans blew through their savings to make ends meet. Aggregate savings peaked at $2.1 trillion in August 2021. As of June 2023, the San Francisco Fed estimated that aggregate savings had dropped to $190 billion.

In other words, Americans ran through $1.9 trillion in savings in just two years.

Then they turned to credit cards. Now Americans are hitting their credit limits. Consumer debt has surged to a record $5.06 trillion with over $1 trillion in credit card bills.

Air is leaking out of the credit bubble, spending has slowed, and companies are feeling the squeeze.

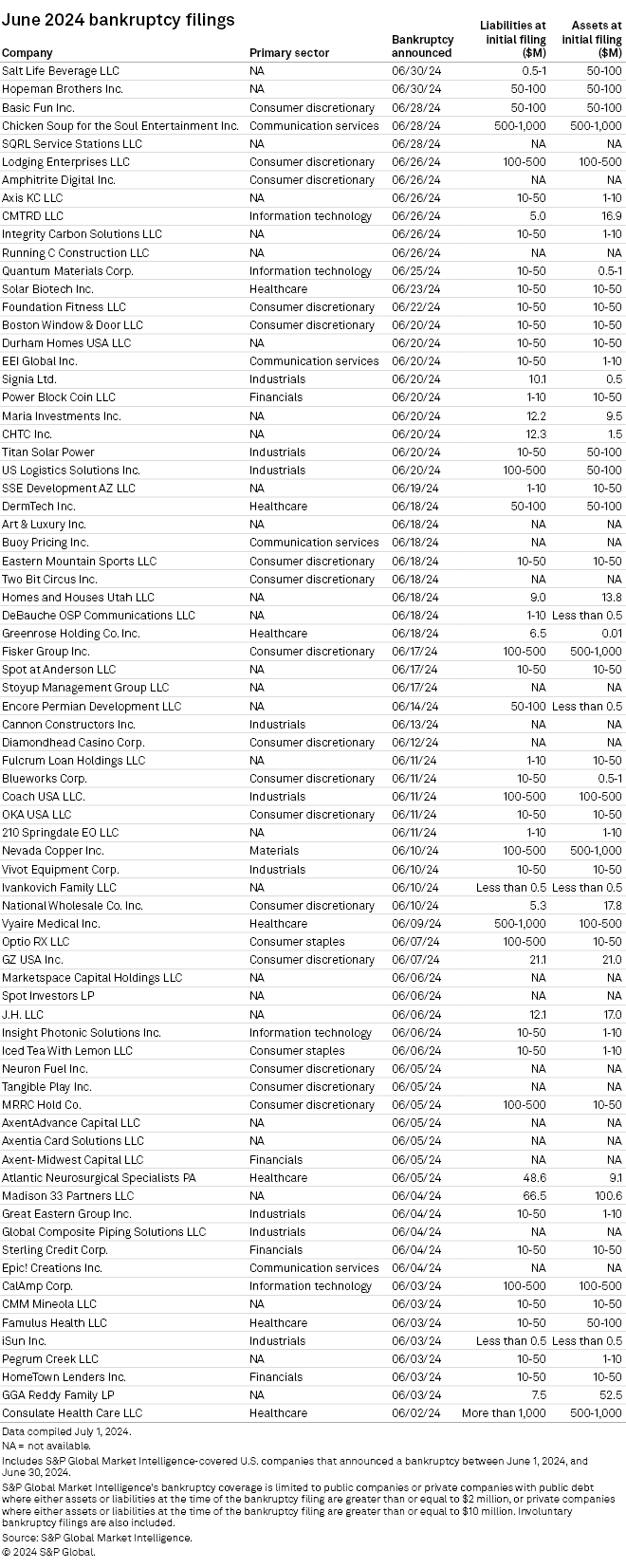

Parsing the corporate bankruptcy filing data, it appears we are in the early stages of an economic meltdown. Most of the filings were in the consumer discretionary sector made up of companies manufacturing goods or providing services that people want but don’t need. The consumer discretionary category includes hotels, restaurants, clothing retailers, sporting goods sellers, media companies, etc.

The data seems to indicate that consumers are cutting back on discretionary spending as they continue to try to make ends meet in this inflationary world.

This is what the beginning of a recession looks like.

According to S&P Global, 55 of the corporate bankruptcies in the first half of 2024 fell into the consumer discretionary category. Sixteen of those filings were in June.

Three of the most recognizable companies in this category to file for bankruptcy in H1 were Red Lobster, Chicken Soup for the Soul Entertainment, and Joann Fabrics.

There were also 40 bankruptcies in the healthcare sector, 40 in industrials, 20 in information technology, 19 in consumer staples, and 16 in the financial sector. The rest of the filings came from the materials, communication services, energy, and utilities sectors.

You will find a complete list of filings through H1 2024 at the end of this article.

The Blood Is on the Fed’s Hands

If you are looking for a scapegoat to blame for the surge in corporate bankruptcies, look no further than the Federal Reserve.

It raised rates and the U.S. economy cannot function long-term in a high interest rate environment. Easy money is gone, and companies are struggling to survive without that mother’s milk.

Or to put it another way, the economy is addicted to the drug of easy money. The drug dealer took it away and now the addict is going through withdrawals.

It’s fair to say the central bank had no choice but to raise rates. After all, price inflation was scorching the U.S. economy. But the real problems started long before the rate hiking cycle – and the Fed caused them too.

In the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, the Fed dropped interest rates to zero and held them there for nearly a decade. It didn’t start trying to normalize rates in earnest until 2017, and it failed miserably. In the fall of 2018, the economy started getting wobbly and the stock market crashed. The Fed paused rate hikes in December 2018 and cut rates three times the following year. The pandemic gave the central bank the excuse it needed to slash rates back to zero in 2020.

The result was well over a decade of artificially low interest rates and money creation.

Other central banks followed the Fed’s lead. More than a decade of easy money had a predictable effect. Corporations, governments, and individuals ran up mountains of debt.

And why not?

Money was cheap, and policymakers gave the impression that the easy money gravy train would never reach the end of the tracks. Everybody just assumed interest rates near zero were the new normal. The Federal Reserve and the U.S. government incentivized borrowing, so people borrowed. After all, incentives matter.

But with all of the money and credit creation, price inflation was also inevitable.

At first, the central bankers at the Fed tried to ignore it, but when it became clear that price inflation wasn’t transitory, the Fed was forced to act.

Now we’re in an untenable environment with debt bubbles as far as the eye can see straining under the pressure of higher interest rates.

This is precisely why the Fed desperately wants to cut rates and will likely deliver a cut in September.

But it will almost certainly be too little too late. The damage is done, just like the damage was already done when the Fed started cutting rates in 2007 attempting to stop the looming meltdown in the housing market. A year later, we got a financial crisis and the Great Recession.

The Fed is stuck between the proverbial rock and hard place. It can ease interest rates, risking a resurgence of price inflation, or it can hold its ground and risk crashing the economy.

The surge in corporate bankruptcies is just one visible crack in the foundation of the economy. There are certainly more we haven’t noticed yet.

That means you should probably hold on to your hats. It’s about to get bumpy.

Mike Maharrey is a journalist and market analyst for MoneyMetals.com with over a decade of experience in precious metals. He holds a BS in accounting from the University of Kentucky and a BA in journalism from the University of South Florida.