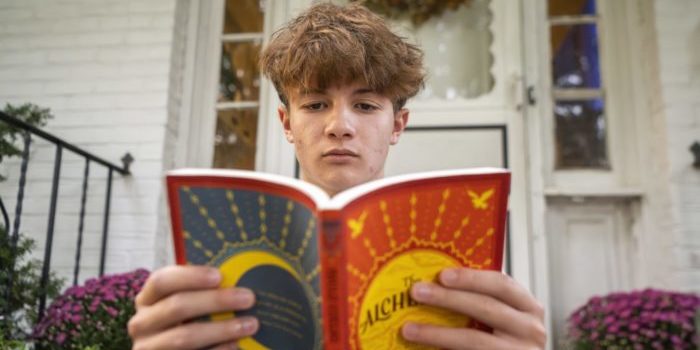

(Headline USA) Chris Stanislawski didn’t read much in his middle school English classes, but it never felt necessary. Students were given detailed chapter summaries for every novel they discussed, and teachers played audio of the books during class.

Much of the reading material at Garden City Middle School in Long Island was either abridged books, or online texts and printouts, he said.

“When you’re given a summary of the book telling you what you’re about to read in baby form, it kind of just ruins the whole story for you,” said Chris, 14. “Like, what’s the point of actually reading?”

At Garden City Middle School, students are required to read several books in their entirety each year, including John Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men and William Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, Principal Matthew Samuelson said. Audio versions and summaries are provided as extra resources, he said.

For Chris, who says he has dyslexia, the audio didn’t make the reading feel more accessible. He just felt bored. He switched this fall to a Catholic school, which his mother feels will prepare him better for college.

A DYING ART

In many English classrooms across America, assignments to read full-length novels are becoming less common. Some teachers focus instead on selected passages—a concession to perceptions of shorter attention spans, pressure to prepare for standardized tests and a sense that short-form content will prepare students for the modern, digital world.

Administrators are also pushing novel pedagogical practices—such as differentiation of classroom assignments according to the unique needs and interests of each individual student—that tend to cater education to the lowest common denominator rather than to challenge students to hit a higher mark by fostering competition.

That leaves the option for those who wish to read the full book to pursue it as extra work; few do.

Even the act of reading to one’s own children has become a point of controversy, since it is considered to give them an unfair advantage over their less literate peers, according to a University of Warwick professor recently profiled by the National Review.

No to this Warwick professor's claim.

If you read to your kids, then you're a good parent.

If you don't, you're a bad parent.

Why?

Because reading is an essential life skill, and parents take on the responsibility of teaching their kids essential life skills.

Also: The bad… pic.twitter.com/TdAIckzNOY— Stephen R. C. Hicks (@SRCHicks) September 5, 2024

Indeed, in the politically correct and reactive world of public education (and in many private schools, as well), teachers struggle to navigate the precarious waters on either end of the ideological spectrum.

On one hand, the cancel-culture movement is alive and well in academia, where Marxist mentality has set its sights on attacking and eradicating the Western, “white male” literary canon.

On the other, conservative leaning groups like Moms for Liberty remain apprehensive about indoctrination and grooming in the classroom—even if the books involved are classic literature such as Romeo and Juliet, which includes several scenes involving sexual innuendo and a love affair between a 14-year-old and an 18-year-old.

In fairness, many teachers have been complicit in pushing inappropriate and indoctrinating texts as substitutions for classic Western literature, in part under the pretense that it may contain similar themes in more accessible language.

But those who are simply proceeding in good faith to try to challenge students as guardians of what pedagogist E. D. Hirsch called “cultural literacy,” and to promote higher-level reading-comprehension and critical-thinking skills, find themselves punished for their efforts.

Lower grade averages, students who are unmotivated and discontented by what they regard as excessive demands (which, in the worst-case scenarios, may lead to chronic disciplinary issues), and consequently, declining test scores due to an emphasis on what are now deemed obsolete skills all ultimately factor into the teacher’s end-of-year performance evaluation.

‘DECENTERING’ THE DULL AND DIFFICULT

The National Council of Teachers of English acknowledged the shift in a 2022 statement on media education, saying: “The time has come to decenter book reading and essay-writing as the pinnacles of English language arts education.”

The idea is not to remove books but to teach media literacy and add other texts that feel relevant to students, claimed Seth French, one of the statement’s co-authors.

Like a growing number of classroom instructors, particularly in humanities-related fields (where many may harbor ambitions for higher-paying administrative jobs), French got his three degrees not in the content field but in educational practice, including a master’s degree specializing in English as a second language. However, he now finds himself influencing curricular changes not only for ESL students but for all students.

In the English class he taught before becoming a dean last year at Bentonville High School in Arkansas, students engaged with plays, poetry and articles but read just one book together as a class.

“At the end of the day, a lot of our students are not interested in some of these texts that they didn’t have a choice in,” he claimed, although many of the students may never have been given the option to challenge themselves in an environment where doing so would not put them at a disadvantage. And in some cases, as with French, teachers may lack the background knowledge to go deeper into the subject material.

The emphasis on shorter, digital texts does not sit well with everyone.

Deep reading is essential to strengthen circuits in the brain tied to critical thinking skills, background knowledge—and, most of all, empathy, said Maryanne Wolf, a cognitive neuroscientist at UCLA specializing in dyslexia research.

“We must give our young an opportunity to understand who others are, not through little snapshots, but through immersion into the lives and thoughts and feelings of others,” Wolf said.

DUMBER AND LAZIER BY DESIGN

There’s little data on how many books are assigned by schools. But in general, students are reading less. Federal data from last year showed only 14% of young teens say they read for fun daily, compared with 27% in 2012.

Teachers now claim the slide had its roots in the COVID-19 crisis, although it was the highly politicized teachers unions that led the demands for school shutdowns, even as evidence emerged that young people had minimal risk of transmitting or suffering severe reactions to the virus without preexisting risk factors.

“There was a trend, it happened when COVID hit, to stop reading full-length novels because students were in trauma; we were in a pandemic,” said Kristy Acevedo, who teaches English at a vocational high school in New Bedford, Massachusetts. “The problem is we haven’t quite come back from that.”

In truth, though, the “literacy” field of education-school pedagogy has been subtly pushing to phase out of classic literature for more than a decade, with COVID becoming just the latest in a long line of excuses for teachers unwilling to do the legwork in school environments where there is greater risk than incentive to challenge students above and beyond the baseline expectations.

This year, Acevedo said she won’t accept that students are too distracted to read. She plans to teach time-management strategies and to use only paper and pencils for most of class time.

Other teachers say the trend stems from standardized testing and the influence of education technology. Digital platforms can deliver a complete English curriculum, with thousands of short passages aligned to state standards—all without having to assign an actual book.

“If admins and school districts are judged by their test scores, how are they going to improve their test scores? They’re going to mirror the test as much as possible,” said Karl Ubelhoer, a middle school special-education teacher in Tabernacle, New Jersey.

For some students, it’s a struggle to read at all. Only around a third of fourth and eighth graders reached reading proficiency in the 2022 National Assessment of Educational Progress, down significantly from 2019.

The influx of new illegal immigrants in the school system under the Biden administration is likely to drive those numbers down even farther, adding a surge of new non-English speakers who must somehow be accommodated and drawing resources earmarked for other students who must negotiate larger and noisier classrooms.

While the in past, there was an assumption that each generation of American students would continue to build on its predecessors, the inverse is also true when it is the schools promoting a lack of personal accountability and responsibility.

Parents who grew up feeling a sense of entitlement in the classroom will convey that to their children and expect the schools to solve whatever problems may arise—assuring that those problems get swiftly brushed under the rug of a bureaucratic jungle with blame shifted to some abstract, politically convenient scapegoat.

Leah van Belle, a literacy advocate in Detroit, said when her son read J.M. Barrie’s Peter Pan in late elementary school, it was too hard for most kids in the class. She lamented that Detroit felt like “a book desert.” Her son’s school doesn’t even have a library.

Still, she said it makes sense for English classes to focus on shorter texts.

“As an adult, if I want to learn about a topic and research it, be it personal or professional, I’m using interactive digital text to do that,” she said.

‘SPINNING PLATES’ AND THE EDUTAINMENT INDUSTRY

Even in well-resourced schools, one thing is always in short supply: time.

Terri White, a teacher at South Windsor High School in Connecticut, no longer makes her honors ninth-grade English class read all of Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird. She assigns about a third of the book and a synopsis of the rest. They have to move on quickly because of pressure for teachers to cram more into the curriculum, she said.

“It’s like spinning plates, you know what I mean? Like it’s a circus,” she said.

She also assigns less homework because kids’ schedules are so packed with sports, clubs and other activities.

“I maintain rigor. But I’m more about helping students become stronger and more critical readers, writers and thinkers, while taking their social-emotional well-being into account,” she said.

In the long run, the synopsis approach harms students’ critical thinking skills, said Alden Jones, a literature professor at Emerson College in Boston. She assigns fewer books than she once did and gives more quizzes to make sure students do the reading.

“We don’t value the thinking time that we used to have. It’s all time we could be on our phone accomplishing tasks,” she said.

Will Higgins, an English teacher at Dartmouth High School in Massachusetts, said he still believes in teaching the classics, but demands on students’ time have made it necessary to cut back.

“We haven’t given up on Jane Eyre and Pride and Prejudice. We haven’t given up on Hamlet or The Great Gatsby,″ Higgins said.

But he said they have given up assigning others deemed to lack the same literary merit and level of interest, such as Charles Dickens’s dense and depressing take on the French revolution, A Tale of Two Cities.

His school has had success encouraging reading through student-directed book clubs, where small groups pick a book and discuss it together. Contemporary authors like John Green and Jason Reynolds have been a big hit.

“It’s funny,” he said. “Many students are saying that it’s the first time in a long time they’ve read a full book.”

Adapted from reporting by the Associated Press