Atop Georgia‘s Stone Mountain on a recent Saturday, hundreds of African Americans, as well as other visitors of color, stood triumphantly overlooking the newly conquered terrain.

They had surmounted the strenuous, one-mile trek to the top despite the hot, August sun—which by mid-morning already felt like it had climbed past 90 degrees.

Likewise, they appeared unfazed by lingering concerns over the coronavirus, for which Atlanta had been named a new outbreak hot-spot.

They were there for recreation and fitness, shouting words of encouragement for other hikers to strive toward the summit: “Almost there!”

Most notably, though, they seemed impervious to the fact that the largest of all Confederate monuments lay in the granite just below their feet.

The bas-relief carving, 76 feet tall and 158 feet wide, features Confederate leaders Jefferson Davis, Robert E. Lee and Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson.

Most hikers turned their attention instead toward the sprawling Atlanta skyline in the distance—itself a symbol of perseverance after the city was burned to the ground during the Civil War.

But the symbolism directly underfoot was hard to ignore in light of a politically-correct focus on rewriting Confederate history during the recent race riots in many cities, Atlanta among them.

A Monument to Progress?

As with other so-called white-supremacist relics, Stone Mountain has been under assault lately from far-left groups.

Online petitions to remove the monument reportedly have garnered thousands of signatures.

Like many Confederate monuments, it was undertaken by the Daughters of the Confederacy in the early 20th century, during a period of national reconciliation that also saw a resurgence of hostile, racist attitudes against blacks.

Several of Stone Mountain’s key supporters and patrons—including the renowned “yankee” sculptor, Gutzon Borglum, and the mountain’s owner, Sam Venable—allegedly had ties to the Ku Klux Klan, which maintained, at the time, a domineering presence in the Democrat party.

On July 4 of this year, just over a month since the Memorial Day death of George Floyd in Minneapolis sparked nationwide social-justice protests, a heavily armed legion of mostly-black protesters made national news by marching on Stone Mountain.

But unlike the violence spurred by domestic-terrorist group Antifa in cities like Portland and Seattle, that demonstration proved, in fact, to be peaceful display of Second Amendment rights.

Regardless of the current controversy, the park surrounding Stone Mountain—a tacky tourist trap boasting miniature golf, a ropes course, a dinosaur attraction and an IMAX theater that plays “The Wizard of Oz”—seems more than ever to be thriving.

In addition to the impracticality of trying to sandblast the massive carving, which could send harmful air-pollutants to the metropolis a mere 20 miles away, allowing the current racial “reckoning” to erase what an earlier wave of popular (albeit detestable) sentiment created is wrong from a long-term historical vantage point also.

Rather, the state—which remains conservative but by an increasingly narrow margin—and the deep-blue enclave of its capital city should lean into an opportunity to make the mountain a testament to true reconciliation, one that marks the evolution of racial progress in Georgia, the South and the nation at large.

Officials should start by ramping up pride in and appreciation for the multifaceted landmark, particularly within the local black community.

Atlanta’s public transportation system, MARTA, comes close to Stone Mountain but could do a better job offering direct access to city residents.

The park might also grant free or reduced rates to those with a local driver’s license (and they can then use the same identification for voting, contrary to the beliefs of failed Georgia gubernatorial candidate Stacey Abrams).

Meanwhile, Gov. Brian Kemp, a Republican, could seek common ground with top Georgia Democrats like Abrams, Atlanta mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms or, perhaps, former President Jimmy Carter, by establishing a panel to consider enhancing the monument with carvings of some of Georgia’s civil-rights heroes, such as the Rev. Martin Luther King and the late Rep. John Lewis.

President Donald Trump might even work with the state to replace the dinosaur park with his National Garden of American Heroes, which he proposed on July 4 during a speech at South Dakota’s Mount Rushmore.

Defending the Confederacy?

Like Stone Mountain, Mount Rushmore is another Borglum-carved granite monument that has faced recent scrutiny from cultural revisionists.

It is worth noting that not a word has been said of effacing South Dakota’s nearby Crazy Horse Memorial, even though the Lakota warriors he led, like the Confederates, took up arms against America’s federal government.

But it is important, also, that in the rush to repudiate its racist legacy, the Confederacy receive a fair shake.

Even those for whom Steven Spielberg’s 2012 film “Lincoln” is the full extent of their historical context can appreciate that slavery, while central to the secession of Confederate states, was ancillary to concerns over the Southern economy and the growing primacy of federal-government intrusion.

Slavery’s advocates at the time largely regarded it as a necessary evil that should be phased out gradually, while abolitionists demanded a more immediate end.

Whether the nation-rending outcome—the effects of which we continue to grapple with—was the best way to proceed will remain a question for the ages.

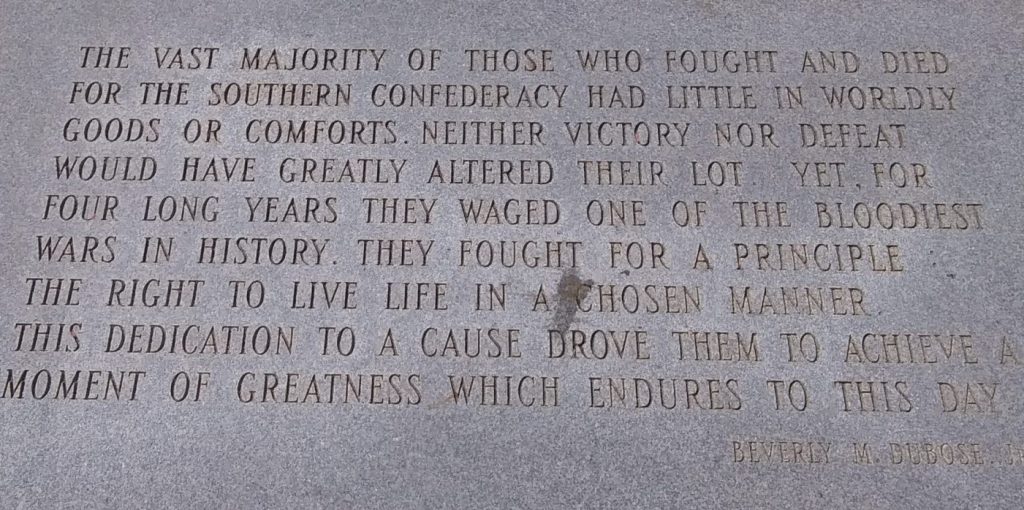

Yet, one of the many markers at Stone Mountain offers an apologia, of sorts, to justify the continued honoring of Confederate soldiers who had little personal stake in the terrible institution.

Most were, themselves, only a rung or two above slaves on the social ladder.

“The vast majority of those who fought and died for the Southern Confederacy had little in worldly goods or comforts,” noted historian Beverly M. DuBose Jr.

“Neither victory nor defeat would have greatly altered their lot,” Dubose said. “Yet, for four long years they waged one of the bloodiest wars in history. They fought for a principle. The right to live life in a chosen manner. This dedication to a cause drove them to achieve a moment of greatness which endures to this day.”

It is fitting, of course, that Trump—a Northerner and political outsider with a penchant for Congress-defying executive action—has sought to reclaim the party of Lincoln.

Trump is even discussing the possibility of delivering his forthcoming Republican acceptance speech on the hallowed grounds of the Gettysburg battlefield, where Lincoln delivered his most famous address.

Trump’s critics, meanwhile, have behaved more and more like the Confederates: taking up arms in rebellion against federal authority and even threatening to secede if Trump wins re-election.

Perhaps the reason the Left holds symbols like Stone Mountain in contempt isn’t that they see the country evolving beyond it, but that such reminders cut too deeply into Democrats’ own shameful legacy and the residual racial prejudices that they, themselves, may harbor.