(Mike Maharrey, Money Metals News Service) Everybody wants to know when the Federal Reserve is going to declare victory over price inflation and begin loosening monetary policy.

The real question is – when are they going to make monetary policy tight again?

Because despite all the worry about high interest rates, monetary policy remains relatively loose.

Sure, hiking rates by 500 basis points is significant, especially in an economy loaded up with debt. And rolling a little over $1.4 trillion off a central bank balance sheet is nothing to sneeze at.

But given the amount of inflation the Federal Reserve created over the last decade-plus, the Fed’s war against inflation amounts to shooting paper wads at a Panzer division.

The Fed Knows Monetary Policy Isn’t Tight

The Fed people know monetary policy isn’t particularly tight. They have their own index that tells them so.

The Chicago Fed’s National Financial Conditions Index (NFCI) “provides a comprehensive weekly update on U.S. financial conditions in money markets, debt and equity markets, and the traditional and ‘shadow’ banking systems.”

As of March 22, the NFCI stood at –0.56. The negative number tells us that monetary policy conditions are loose from a historical perspective.

As the Chicago Fed explains, “Positive values of the NFCI have been historically associated with tighter-than-average financial conditions, while negative values have been historically associated with looser-than-average financial conditions.”

So, despite its efforts and a lot of jawboning, the Fed still hasn’t pushed monetary policy over the edge too tight. That means this has been a pretty lame inflation fight.

Balance sheet reduction tells the same story.

Yes, the Fed has managed to shrink the balance sheet by almost $1.5 trillion. That sounds impressive until you remember that the Fed added nearly $5 trillion during the pandemic. That was on top of the massive $4 trillion blowup of the balance sheet during the Great Recession that the Fed could never run off as promised.

In effect, the balance sheet runoff is a little like taking a bucket of water out of my pool.

In fact, the balance sheet reduction plan was pretty tepid to begin with.

Based on the central bank’s balance sheet reduction plan announced in March 2022, it would take 7.8 years for the Fed to shrink its balance sheet back to pre-pandemic levels. That doesn’t even begin to touch the trillions added to the balance sheet in the decade after the 2008 financial crisis.

The Gorilla in the Fed’s Meeting Room

I’m not the only one who has noticed this inconvenient truth.

Bloomberg macro strategist Simon White called loose monetary policy the gorilla in the room.

“A famous experiment asks volunteers to watch a video of a basketball game and count the passes. Halfway through, a gorilla strolls through the action. Almost no one spots it, so focused they are on the game. As we count the dots and parse the language at this week’s Fed meeting, it’s easy to miss the fact that policy overall remains very loose despite over 500 bps of rate hikes. The gorilla has gone by largely unnoticed.”

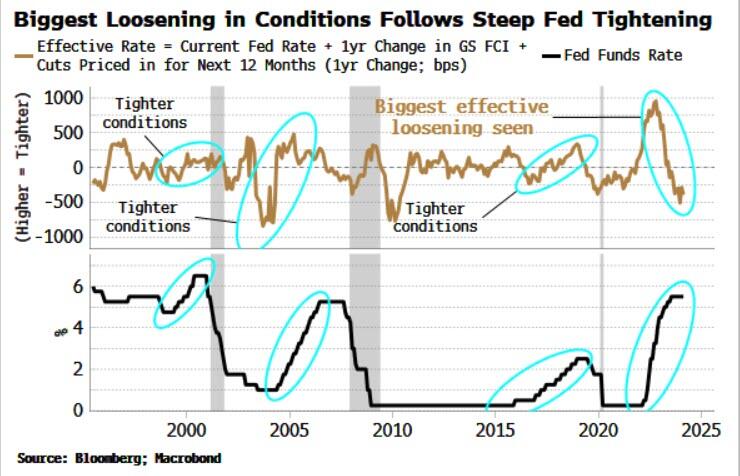

White points out that despite the Fed hiking rates higher and faster than it has since 2000, the effective Fed rate has actually dropped – by more than it has in 30 years!

Let that sink in for a moment. Financial conditions are looser today than they were when the Fed started this so-called inflation fight.

And yet the markets are desperate for rate cuts. They want their easy money liquor back even though their glasses remain half full. The bartenders at the Fed will almost certainly deliver.

As White put it, “The Fed may end up spiking the punch bowl with more booze when the party is already quite tipsy.”

But hasn’t the Fed beaten inflation?

Well, no.

Yes, CPI fell from its high of 9.1 percent in the summer of 2022. But even taking CPI at face value, price inflation remains sticky.

And you really can’t take CPI at face value.

Inflation is worse than the government data suggest. The government revised the CPI formula in the 1990s so that it understates the actual rise in prices. Based on the formula used in the 1970s, CPI is closer to double the official numbers. So, if the BLS was using the old formula, CPI peaked closer to 18 percent. And using an honest formula, it would probably be worse than that.

To beat down price inflation, interest rates need to rise above CPI. Based on a more honest CPI formula, the Fed never got close.

This may explain why cyclical price inflation remains elevated.

The San Francisco Fed splits core PCE (The Fed’s favorite price inflation measure) into two components – cyclical and acyclical. As White explains, the components making up cyclical price inflation are more sensitive to Federal Reserve interest rate policy.

“While acyclical inflation has fallen all the way back to its pre-pandemic average, cyclical PCE remains at its 40-year highs. The Wizard of the Fed has been pulling the rate-hiking levers, but they have done little to directly quell inflation.”

Borrowing costs also reveal Fed monetary policy remains loose. As part of its revision campaign, the BLS removed mortgage costs from the CPI in 1983. It stripped out car repayments in 1998.

Larry Summers and other economists from Harvard and the International Monetary Fund reconstructed the CPI to include these borrowing costs for a paper published in February 2024. According to their calculations, inflation not only peaked higher than it did in the 1970s, but it continues to run around 8 percent – far above the headline 3.2 percent CPI reported in February.

White sums it up this way:

“Gorillas playing basketball is a very odd thing; the Fed cutting rates before the last quarter of this year would be even odder. Before then, though, markets are likely to try to re-impose some sobriety by reducing or eliminating the number of rate cuts priced in.”

The Fed Hasn’t Done Enough to Win the Inflation Fight

White reveals an ugly truth – the Fed hasn’t done enough to win this inflation fight and any declaration of victory is actually a surrender.

Looking at how Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volker handled the 1970s and 80s inflation is informative.

Volker went on the warpath in 1980 and raised rates to 20 percent. At the time, CPI was in the 14 percent range. CPI didn’t return to 2 percent until 1986. At that point, the average Fed funds rate was 14.35 percent. Even with that, the CPI spiked back up for several years in the late 80s and early 90s.

You’ll notice that Volker drove rates significantly above the CPI. But Powell is no Volker. You can claim that the Fed drove rates modestly above CPI, but as we’ve seen, it’s all smoke and mirrors.

Monetary policy is still loose.

The problem is raising rates was still enough to pop bubbles and break things. Easy money is the mother’s milk of this debt-riddled economy. And while Fed policy isn’t tight, it is tighter – too tight for the level of debt.

It’s only a matter of time before the crisis manifests.

As I’ve said on my podcast, the Fed is between a rock and a hard place.

On the one hand, it can choose to stick to its guns, keep rates higher for longer, and bring down inflation. But that will almost certainly drag the economy into a crisis.

On the other hand, it can pick inflation and maybe rescue the economy.

And the reality is we may get both the rock and the hard place – stagflation.

Mike Maharrey is a journalist and market analyst for MoneyMetals.com with over a decade of experience in precious metals. He holds a BS in accounting from the University of Kentucky and a BA in journalism from the University of South Florida.