(Ken Silva, Headline USA) The FBI recently released its file on deceased Cleveland Browns football legend Jim Brown, revealing that agents monitored Brown’s First Amendment-protected activity as he was funding a film about the black nationalist movement.

The FBI’s illegal surveillance of Brown was part of COINTELPRO—its 1960s-era operation where undercover agents infiltrated and subverted American anti-war and civil-rights organizations. COINTELPRO was exposed by in the 1970s by the Church Committee during its investigation into abuse by the FBI, CIA and other federal agencies.

According to the FBI documents released Friday, the U.S. government was concerned about a film project Brown was helping fund in the late 1960s.

“This movie was made in Cleveland, largely through the influence of Jim Brown, former Cleveland Browns football player and current member of the Negro Industrial Economic Union,” an Aug. 1, 1968, FBI memo said.

“Brown wanted it made in Cleveland so as to provide part-time employment for as many Black Nationalist youth as possible.”

The documents also reveal that the FBI had spies throughout the movie industry.

Citing an undercover informant in the motion picture industry, the August 1968 FBI memo gave a synopsis of Brown’s film, Uptight—a film about how black revolutionaries being betrayed by one of their own.

“The picture involves the Negro neighborhood and Negro activities in Cleveland, Ohio, and portrays two distinct groups of Negroes, being the militant and violent types compared to the peaceful group, both groups attempting to obtain civil rights for Negroes through their respective means,” the memo said.

“The picture starts with the militant violent grows stealing guns and ammunition from gun shops, and the implication is that this stealing is condoned. The picture ends with the principal character, Tank, who is connected with the militant group, walking across a bridge at a steel company, jumping off, and committing suicide,” the memo said.

Another spy told the FBI that “90 percent” of people involved with the movie opposed its messaging, fearing that it would “incite Negroes to riot.”

“However, Jim Brown [and the film’s director] reportedly saw this movie as a means for the Negroes to ‘get back at the white people,’” the memo said.

The memo also reported turmoil on the set.

A rival black nationalist group was apparently upset that Brown didn’t hire them to work on the film. This reportedly angered the director, who left Cleveland and finished filming Uptight elsewhere, according to the memo.

The film came out later that year.

Two years later, records indicate that the FBI was still spying on Brown, this time in his capacity as the head of the the Cleveland-based Black Economic Union.

According to a June 1970 memo, agents were concerned that Brown’s Black Economic Union was serving as a front group for Harrel Jones, the leader of the Black Nationalist Party for Self-Defense.

At the time, Cleveland’s Council of Churches and a group called Cleveland Now had given the Black Economic Union a $20,000 grant to “fight drug abuse.” But in reality, that money was being secretly funneled to Jones, according to FBI records.

The June 1970 memo advised the FBI to leak information about the $20,000 grant to the local media, in an attempt to sabotage the payment to Jones.

“Cleveland recommended information concerning the devious means of furnishing funds to the head of [Black Nationalist Party for Self-Defense] be leaked to an established news media source in an effort to deter further funding of this black extremist group,” the memo said.

“It is felt that this information can be linked to the news media without embarrassment to the Bureau, and Cleveland recommends that this action be followed,” the memo said, outlining a tactic of subversion that was typical for COINTELPRO.

Records don’t indicate how the matter was resolved. They do detail Jones’s private protection service, where his black nationalists would patrol Cleveland neighborhoods.

An undercover informant told the FBI that Jones was asking for local businesses to pay a $25 fee. In exchange, the businesses could place a sticker in their window, warning that “any criminal who might intend to victimize this particular business would have to deal with the Afro Set Community Patrol,” the memo said.

Jones was apparently approached by special agents about his protection racket, and he spoke to them about it.

“He stated that he had obtained a truck for the purpose of protecting the community. He stated that he had already begun patrolling the inner city and stated that he was policing the Rainbow Terrace Extension Apartments on Kinsman Road, Cleveland,” a separate June 1970 FBI memo stated.

“He stated that four or five members of the Afro Set lived in these apartments and were in charge of its security force,” the memo said.

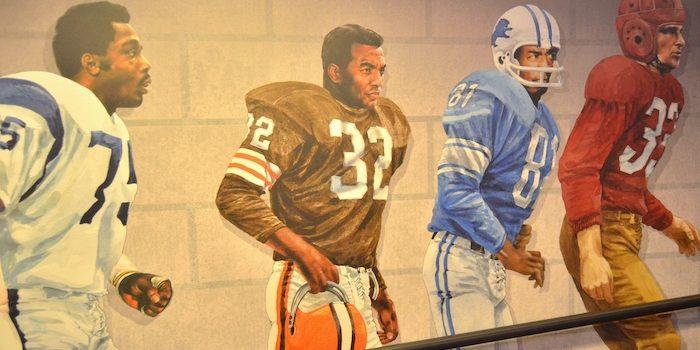

Brown was recognized as the AP NFL Most Valuable Player three times, and won an NFL championship with the Browns in 1964.

He died on May 18.

Ken Silva is a staff writer at Headline USA. Follow him at twitter.com/jd_cashless.