(Headline USA) The drastic about-face from mainstream media in coverage of the US border crisis was immediately clear in their refusal to cover the atrocious conditions in migrant detention centers, newly reopened and overcrowded under President Joe Biden.

These cages are not only ignored with a casual disinterest, however. The Biden administration is now shamefully attempting to put a positive spin on its violations of federal immigration law while brazenly refusing access to the worst facilities—even to lawmakers from the opposing party.

To a large extent, media like the far-left Associated Press are playing ball, allowing them to claim that the processing centers for thousands of unaccompanied minors are more like boarding schools.

A breeding ground for the coronavirus where physical and sexual assaults have reportedly run rampant—these facilities now exemplify “model” conditions for the asylum seekers, whom Democrats hope to import and quickly grant citizenship in order to assure a new generation of voters.

It is a stark contrast from the position taken even as recently as 2018, when a wave caravans organized by left-wing activists sought to overextend the existing border security operations and radical members of Congress like Rep. Alexandria Ocasio–Cortez, D-NY, made efforts to visit and pretend to weep at the sight.

Ocasio–Cortez referred to them as being like “concentration camps” at the time—a talking point her fellow Democrats and media allies desperately tried to make stick in the leadup to the midterm election for the Trump administration.

The AP’s recent reporting on one such facility is included below in its unedited context:

Teenage boys chased down soccer balls on grassy fields. Dormitory beds were organized into small pods with a TV in each section. Some kids laid on the cots reading, while others played cards nearby with caseworkers.

The Biden administration on Friday gave a rare look inside an emergency shelter it opened to house migrant children who crossed the U.S.-Mexico border alone, calling the California facility a model among its large-scale sites.

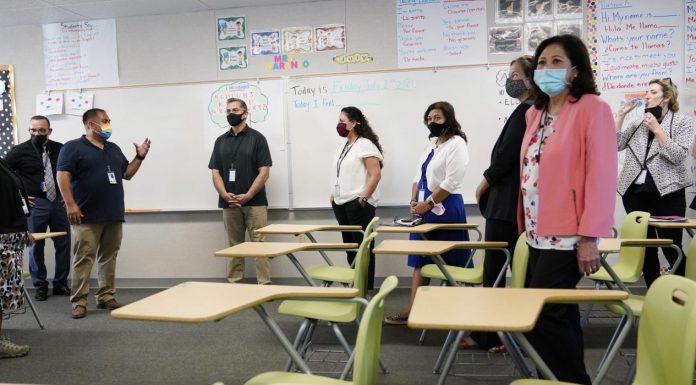

Health and Human Services Secretary Xavier Becerra, whose agency is in charge of caring for migrant children, was joined by elected officials as he toured the shelter housing nearly 1,400 children at the Los Angeles County fairgrounds in the city of Pomona. Two journalists from The Associated Press were allowed to accompany them and shared notes and photos of the tour with other news outlets as part of a pool arrangement.

The facility was a sharp contrast to conditions reported at other emergency shelters, where children have complained of foul-smelling food, little outdoor recreational space and having to spend their days sleeping with little to do and no knowledge of when they would be released to relatives in the United States.

“We consider this a model,” Becerra told reporters after touring the Pomona facility, which has a 30,000-square-foot (2,787-square-meter) air-conditioned room with foosball and ping pong tables, wooden blocks and other games. Large signs in Spanish above the room’s entryway read “welcome,” “hope,” and “love.”

In a room filled with caseworkers, Becerra spoke to the kids in Spanish about when they would be reunited with their families.

“We are trying to do this as soon as possible, but in a safe manner,” he said.

Within four hours of arriving at the shelter, each child can use the call center, a room with brightly colored paintings of butterflies and sea creatures. After that, they can call their families twice a week.

Next to the call area, scores of blue, pink and silver stars with names nearly covered a wall. An official said staffers post a star with a child’s name when they are discharged from the facility.

“You’re running out of space,” Becerra noted.

Staff at the shelter roam the dorms and outdoor spaces to be on alert for any emergencies. Teachers from the Pomona Unified School District provide 90-minute classes twice a week to each child, with half the time spent developing their English skills.

With its existing buildings and green spaces, the Pomona site had some advantages over places like Fort Bliss Army base near El Paso, Texas, where the government’s largest shelter was erected as a tent camp from scratch, Becerra said. Advocates have said Fort Bliss, which Becerra visited days ago without allowing media to accompany him, has been particularly problematic.

“It is not easy to stand something up like this quickly, and do it right, but I think you can see that this is a place where kids can be healthy and safe,” Becerra said of the Pomona facility.

The government set up the temporary shelters this spring as tens of thousands of children crossed the border alone. Of the 14 centers that opened, two have been shuttered because they did not meet government standards; others have been closing as more children are released to family in the U.S. or to facilities with higher levels of care.

While the emergency shelters are widely considered an improvement over border holding facilities packed with kids, the Biden administration is facing increasing pressure to address concerns that migrant children have been languishing in the unlicensed centers rather than being quickly reunited with their families in the United States, causing anxiety and panic attacks.

Republicans say the administration was caught flat-footed by the situation at the border and that President Joe Biden’s immigration policies have encouraged unaccompanied children to come. Nearly 19,000 children traveling alone were picked up along the border in March, by far the highest month on record.

Advocates say no shelter can replace a family or licensed facility in terms of providing care for children. They say the emergency sites were meant to be a safe place to house children for a couple of weeks to give the government time to contact and vet their relatives. Those without family in the U.S. are supposed to be sent to a state-licensed facility.

As of this week, the average stay at temporary shelters was 37 days, with the network of facilities filled at just over half its capacity, according to Health and Human Services data obtained by the AP.

More than half of the 5,300 children at emergency shelters have close family in the U.S. such as a parent or grandparent. No such contact was identified for a third of the youth at those sites, the data showed.

Immigration attorney Karina Ramos of Immigrant Defenders Law Center in California visits the Pomona shelter twice a week. Of the 2,605 children who have come there, more than half have been reunited with their families, Becerra’s agency said.

“The number one question is: ‘When am I going home?’” Ramos said, which is “obviously understandable.”

But Ramos said the children generally don’t have complaints. Most at the Pomona facility are teenage boys, with fewer than 300 children under 12. Most are from Guatemala and Honduras.

“This is definitely not Fort Bliss,” Ramos said. “Children are generally active, and they’re happy, and they come talk to us.”

In transcripts of interviews done by attorneys from March to early June and filed in federal court in Los Angeles, more than a dozen migrant children described their desperation to get out of the emergency facilities. In one account, a teenage girl said she had been at Fort Bliss for nearly 60 days and had resorted to eating only popsicles and juice because the food was foul.

Becerra said conditions have improved in recent weeks with additional spiritual, recreational, educational and mental health services. The Fort Bliss shelter also was being reconfigured to a more child-friendly pod system with single cots instead of doubles. More caseworkers have been added, speeding up family reunifications.

Because of the progress, Becerra said the number of children his agency is caring for has dropped from a high of more than 22,000 to just over 14,400, with more than half at licensed shelters. His agency said it will close four emergency facilities this summer, with Pomona and Fort Bliss staying open.

Adapted from reporting by the Associated Press