(Mike Maharrey, Money Metals News Service) The Federal Reserve put interest rate cuts on pause at the January meeting. The central bankers cited expanding economic activity and a stable labor market as reasons for the pause.

The official FOMC statement asserted that while “job gains have remained low, the unemployment rate has shown some signs of stabilization.” In his post-meeting press conference, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell repeatedly characterized the labor market as “stable,” insisting economic activity has been “expanding at a solid pace.”

When you listen to the central bankers at the Fed, it’s clear they pay a lot of attention to employment data. This should concern you because that data seems about as reliable as a politician’s campaign promise.

If you just read the headlines, you likely believe the job market is in pretty good shape. Every month, the Bureau of Labor Statistics tells you that a lot of jobs were created. The media trumpets these numbers and politicians lean on them to prove how great they are.

For instance, the media lauded the January BLS report as “a shock to the upside.” According to the bureau, the economy added 130,000 jobs. The forecast was for around 70,000 new jobs.

That’s great! right? This confirms what the Fed people said! The labor market is humming!

Sure. Sounds good. But just wait for the revisions.

Because, ladies and gentlemen, there will be revisions.

In fact, there were revisions in the latest data release. And they should have garnered the headlines, not the January number.

At the same time that the BLS announced this shockingly good job growth, it revised the December number down from 50,000 to 48,000 new jobs.

But that was just a warmup. The bureau also made its end-of-the-year adjustment to the “birth-death model” it uses to determine job growth. That erased nearly half a million jobs from the economy. To be precise, the BLS wiped out 403,000 jobs with its model revision.

With the revision, the U.S. economy only generated an average of 15,000 jobs per month in 2025. You probably don’t have that impression if you just saw the headlines as the BLS announced its employment data each month.

If it sounds like the agency is just making stuff up, well…

And even if you give the folks over at the BLS the benefit of the doubt and assume they’re doing the best they can, their best is pretty abysmal.

In fact, downward revisions are standard operating procedure for the BLS. The agency had already erased nearly 1 million (911,000) jobs that it initially claimed were created between March 2024 and June 2025.

So, what are we to make of the January report claiming the economy added a surprising 130,000 jobs?

Nothing.

Because some of these jobs will almost certainly be erased next month.

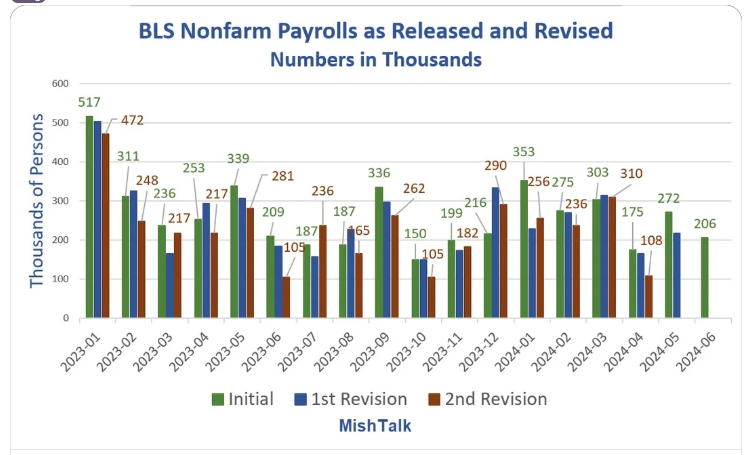

The BLS has a long history of reporting rosy job numbers only to quietly come back and revise them downward down the road. In 2023, job numbers were revised down in 10 of the 12 months.

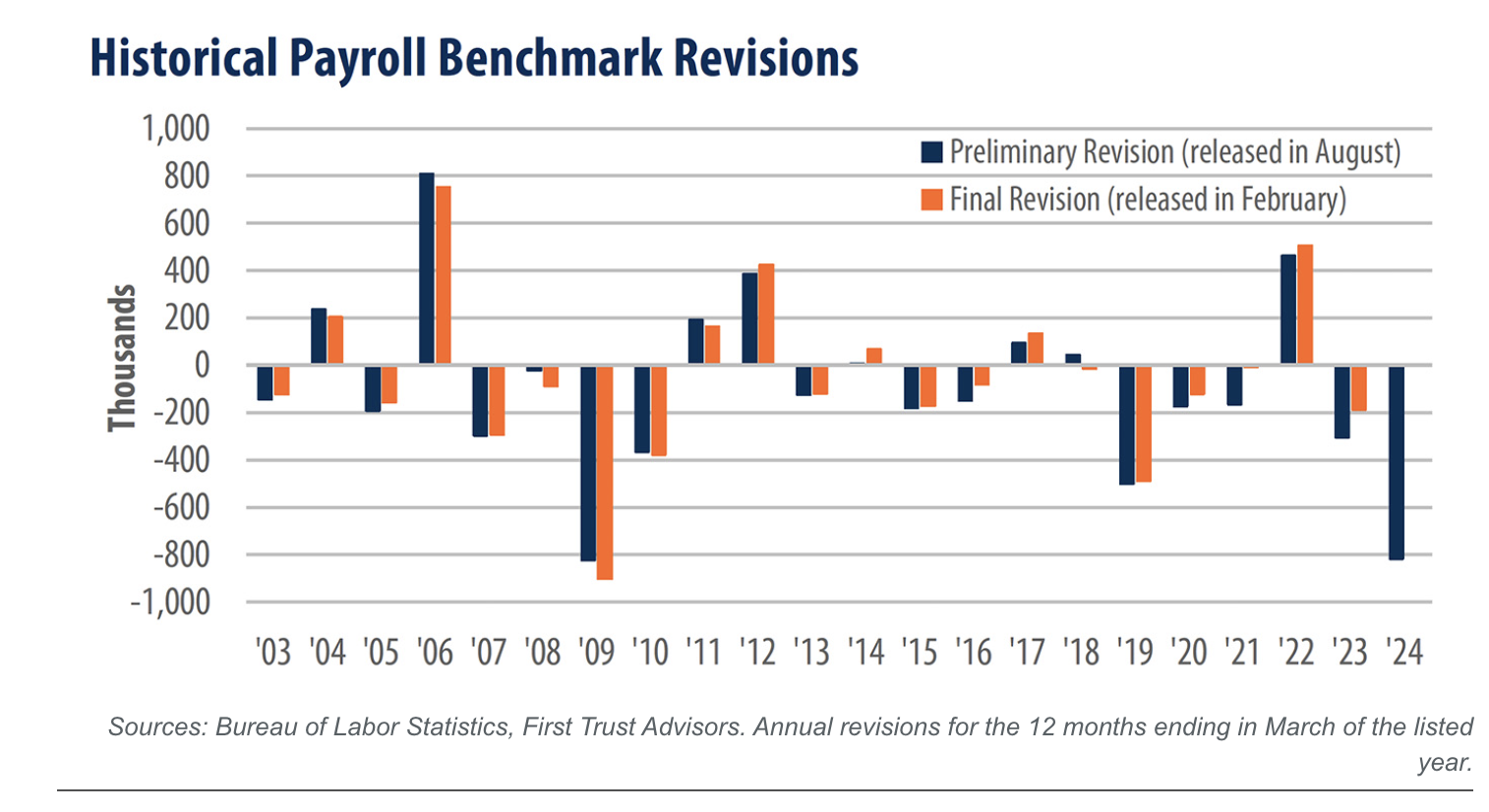

To be fair, compiling employment data is no simple task. Revisions should be expected. But why do the updates almost always remove jobs from the economy? One would think you’d see upward revisions nearly as often as downward, right?

Nope.

Since 2003, the final annual BLS numbers were lower than the initial report 14 times compared to seven upward revisions.

It’s almost as if the agency is trying to make the government look good.

If that’s the strategy – it works.

It’s notable that markets only react to the initial numbers. You never see markets tank because the BLS erased a bunch of jobs from the economy with a few clicks of its calculator. The revisions happen quietly in the back alleys. Nobody pays any attention to them. That creates the illusion that the labor market is much stronger than it is.

It goes something like this:

This month, the government reports good news. Everybody celebrates. Markets move. The following month, the government quietly revises everything downward and reports that the good news was really bad news.

And nobody pays attention.

This wouldn’t matter nearly so much if central bankers and government officials didn’t lean so much on this data to make decisions. But they do. And if the data is this unreliable, what does that tell you about the decisions based on this data?

Let’s be honest; when you look at the history, one’s got to wonder why anybody takes these numbers at face value.

The lesson here is that we need to be somewhat skeptical of government data. And we need to pay attention – not just to the headline release, but the revisions as well.

Mike Maharrey is a journalist and market analyst for Money Metals with over a decade of experience in precious metals. He holds a BS in accounting from the University of Kentucky and a BA in journalism from the University of South Florida.