(Mike Maharrey, Money Metals News Service) They buried the lede.

The Federal Reserve loosened monetary policy significantly during the March FOMC meeting that wrapped up Wednesday.

“But wait,” you say. “The Fed held interest rates steady, right?”

Yes. Yes, they did.

The federal funds rate remains set between 4.25 and 4.5 percent. And that was the headline on virtually every mainstream report about the meeting. But that wasn’t the most significant news coming out of the Fed meeting.

So, was the big news that the Fed still anticipates two rate cuts in 2025?

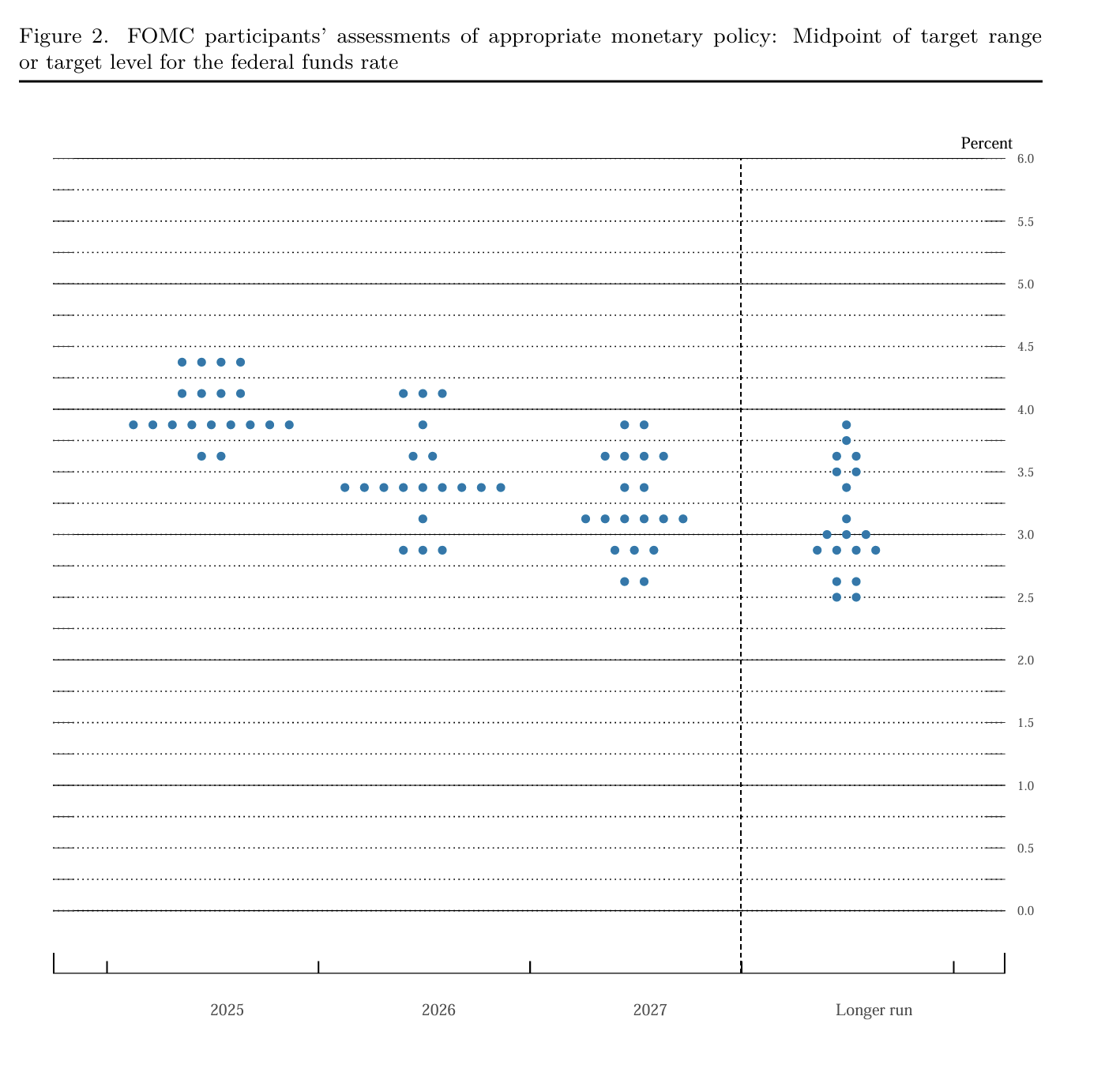

That’s true as well. The FOMC released a new dot plot charting the anticipated trajectory of rates over the next couple of years. The majority of committee members expect a 50-basis point easing of rates this year.

However, Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell left plenty of wiggle room for a shift in policy – in either direction.

“If the economy remains strong, and inflation does not continue to move sustainably toward 2 percent, we can maintain policy restraint for longer. If the labor market were to weaken unexpectedly, or inflation was to fall more quickly than anticipated, we can ease policy accordingly.”

But that wasn’t the big news either.

So, was it the fact that Powell & Company seems really worried about the impact of tariffs?

Well, they are certainly setting up tariffs as a scapegoat for any future resurgence in price inflation. The FOMC statement noted that “uncertainty around the economic outlook has increased,” and during his post-meeting press conference, Powell said, “I do think with the arrival of the tariff inflation, further progress may be delayed.” Powell also claimed that a “good part” of the central bank’s higher inflation expectation comes from tariffs.

However, the fundamental cause of price inflation is monetary policy. Tariffs will put upward pressure on a lot of prices. This will be reflected in the CPI. But tariffs don’t raise all prices. (You can read a detailed explanation of tariffs and inflation here.)

An increase in the supply of money and credit is the source of generalized price inflation. Monetary inflation causes the general price level to rise. Price inflation is a symptom of monetary inflation.

Given that the central bank never did enough to unwind the massive amount of monetary inflation it created in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis and during the pandemic, it will need a convenient scapegoat when price inflation remains above its mythical target.

But that wasn’t the big news either.

The Big News

As I mentioned the Federal Reserve did make a big move during the March meeting, but it largely flew under the radar.

The Fed will drastically slow its balance sheet reduction process beginning in April.

Instead of allowing $25 billion in Treasuries to roll off the balance sheet each month, it will cap the runoff at $5 billion.

In other words, the runoff of Treasuries will slow to a snail’s pace.

The $35 billion cap on the reduction of mortgage-backed securities will remain in place, although the central bank has rarely hit that level.

This is a significant loosening of monetary policy. In fact, I would argue it is far more significant than a quarter-percent rate cut. As one analyst told CNBC, “The Fed indirectly cut rates today by taking action to reduce the pace of runoff of its Treasury holdings.” [Emphasis added]

Inflation and the Fed Balance Sheet

The balance sheet serves as a direct pipeline to the money supply. When the Fed buys assets – primarily U.S. Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities – it does so with money created out of thin air. Those assets go on the balance sheet and the new money gets injected into the financial system and ultimately the broader economy.

This process is known as quantitative easing (QE).

Before the 2008 financial crisis and Great Recession, the balance sheet was just over $900 billion. By the end of the pandemic era, it stood at just under $9 trillion.

In other words, the Fed pumped over $8 trillion into the economy in 14 years through QE alone. That was on top of the money created by bank lending incentivized by artificially low interest rates.

When Ben Bernanke launched the first round of QE at the onset of the Great Recession, he assured Congress that the Fed was not monetizing debt. He said the difference between debt monetization and the Fed’s policy was that the central bank was not providing a permanent source of financing. He said the Treasuries would only remain on the Fed’s balance sheet temporarily. He assured Congress that once the crisis was over, the Federal Reserve would sell the bonds it bought during the emergency.

That never happened.

And then the Fed doubled down, expanding the balance sheet by nearly $5 trillion during the pandemic.

This is, by definition, inflation.

The Fed announced a balance sheet reduction plan in March 2022 when it could no longer convince everybody that price inflation was “transitory.” The plan wasn’t exactly ambitious given the amount of inflation it created during the pandemic. If the Fed followed the blueprint (and it didn’t), it would take 7.8 years for the Fed to shrink its balance sheet back to pre-pandemic levels. This doesn’t even account for the trillions added in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis.

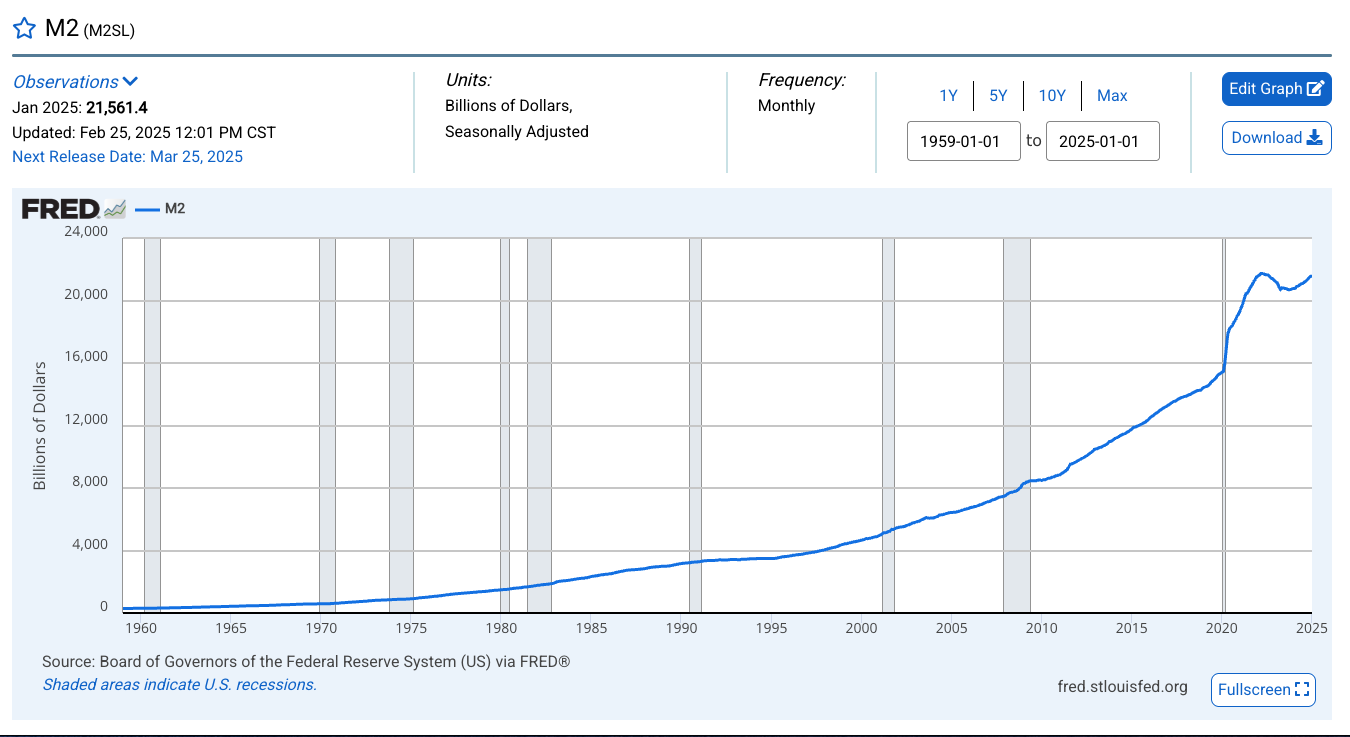

The money supply began shrinking in April 2022 due to a combination of quantitative tightening and interest rate hikes. (The first hike of the cycle was in March 2022.)

The M2 money supply bottomed in October 2023 at $20.69 trillion. Since then, it has crept upward. As of January, it was at $21.56 trillion. That’s the highest level since January 2022.

In other words, despite all the talk about fighting price inflation, the central bank has been creating monetary inflation (the cause of price inflation) for over a year.

And it just announced plans to speed up that process.

That should be the headline coming out of this Federal Reserve meeting.

Why Slow Balance Sheet Reduction Now?

Given the concerns about sticky price inflation and the conceding that the path forward appears murky at best, why would the central banker make such a significant easing move now?

It’s the national debt, my friends.

The Fed telegraphed this policy shift in the minutes of the January FOMC meeting, which according to Reuters “showed central bankers concerned about how the effort to shed bonds might collide with dynamics around the federal debt ceiling.” Based on the minutes, “various” policymakers said they were open to pausing or slowing the reduction of Fed-owned Treasury and mortgage bonds to navigate uncertain money market conditions as Congress sorts out government finances and a statutory cap on the federal debt that came back into force last month.”

The federal government ran up against the debt ceiling at the beginning of the year. In effect, it means the government can’t borrow any money until Congress raises the ceiling. (You can read more about the debt ceiling, its history, and its ramifications HERE.)

To keep funding federal deficits, the U.S. Treasury is employing “extraordinary measures,” that include pausing some funding, along with redeeming existing investments and suspending future investments in the Civil Service Retirement Disability Fund, the Postal Service Retiree Health Benefits Fund, and federal employee retirement system savings plans. These moves would likely push the hard debt ceiling deadline to the summer of 2025.

However, the current situation is driving “unsettled” money market conditions. According to Reuters, this “increases the risk the Fed could go too far with liquidity withdrawals, something central bank officials do not want, and which opens the door to a shift in the QT process.”

And here we are.

Done deal.

Trying to Have It Both Ways

The Federal Reserve is trying to have its cake and eat it too. On the one hand, it held interest rates steady and said all the right things about inflation worries. On the other hand, it just loosened monetary policy significantly.

This further underscores the Catch-22 facing the Federal Reserve. It simultaneously needs to hold rates higher for longer to rein in price inflation and cut rates due to the excessive levels of debt and malinvestments in the economy. Obviously, it can’t loosen and tighten monetary policy at the same time.

The Fed is balanced precariously on a tightrope. The question is which way will it fall?

Mike Maharrey is a journalist and market analyst for Money Metals with over a decade of experience in precious metals. He holds a BS in accounting from the University of Kentucky and a BA in journalism from the University of South Florida.