(Mike Maharrey, Money Metals News Service) Supporters of tax cuts argue that they eventually “pay for themselves” and lower deficits through economic growth and increased revenue, even without significant spending cuts.

Recent history casts doubt on this claim.

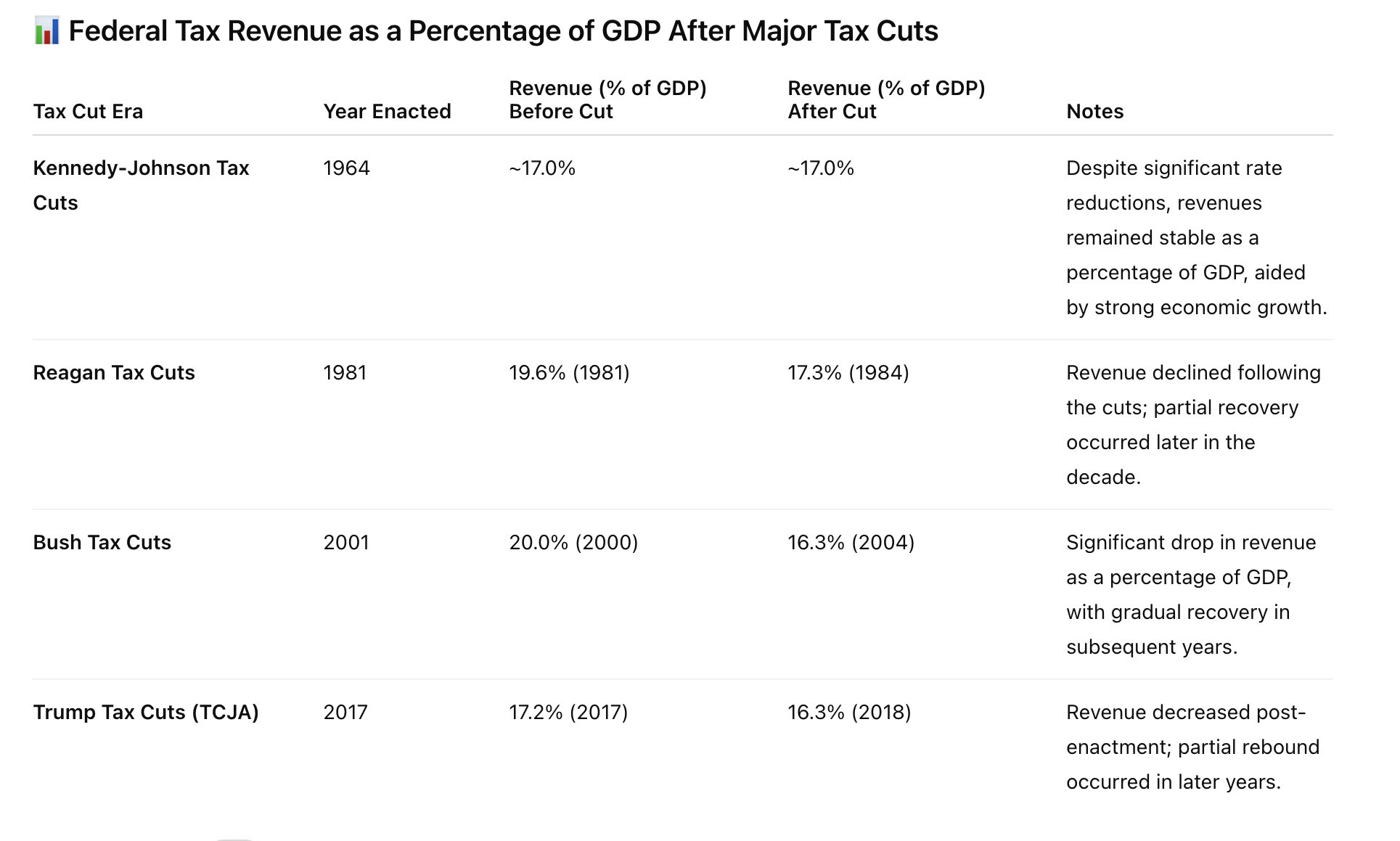

Examining the three major tax cuts over the last 50 years, after initially dropping, revenue ultimately rose in subsequent years and eventually exceeded pre-tax cut levels in nominal terms; however, revenue as a percentage of GDP fell in the aftermath of the cuts.

In the meantime, spending ballooned faster than revenue rose, erasing the modest impact of growth-related revenue generation.

This underscores a crucial point: Uncle Sam doesn’t have a revenue problem. It has a spending problem.

And there is little will to address that problem.

The Big Beautiful Bill

It’s easy to talk about cutting government spending and reining in deficits.

It’s tough (if not impossible) to cut government spending and rein in deficits.

This is why every presidential administration since Herbert Hoover’s has left the country deeper in debt at the end of its term than when it started.

The One Big Beautiful Bill Act (yes, that’s the actual name) is a great example of this phenomenon.

The bill features 1,042 pages of spending cuts, spending increases, and tax cuts. While the legislation trims some outlays, it increases others, and it ultimately falls far short of addressing the surging budget deficits and ballooning national debt.

According to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), the bill would add $2.4 trillion to the budget deficit over 10 years.

Proponents of the bill claim the CBO is understating the tax cuts’ stimulus effect and argue that economic growth will “pay for” the tax cuts and ultimately narrow the deficit.

Can We Grow Our Way Out of Debt?

The conservative theory is that tax cuts “pay for themselves” and will ultimately lower deficits due to the fact that they incentivize work and investment, thus boosting productivity. While tax rates are lower, they are applied to higher levels of income, keeping total tax revenues steady and even increasing them over time. This theory was popularized in the 1980s by the Laffer Curve.

How does this theory play out in practice?

Over the last 50 years, it hasn’t.

There have been three major tax cuts since the 1980s.

- Reagan tax cuts in 1981 and 1986

- Bush Tax cuts in 2001 and 2002

- Trump tax cuts in 2016

In all three cases, federal revenue as a percentage of GDP declined, and the tax cuts ultimately contributed to higher deficits in the absence of spending cuts.

In 1981, Congress slashed the top marginal income rate from 70 to 50 percent and then cut it again to 28 percent in 1986. The U.S. did experience strong economic growth in the mid-to-late 80s, but budget deficits still exploded. Following the cuts, revenue as a percentage of GDP declined, reaching a low in 1984. It improved after that, but did not return to pre-cut levels during the Reagan presidency.

In the meantime, spending exploded.

In 1981, the budget deficit was $79 billion. In Reagan’s last year in office in 1989, it had ballooned to $153 billion. As a percentage of GDP, the deficit grew from 2.5 percent of GDP to 2.8 percent during Reagan’s time in office.

In 2001 and 2003, George W. Bush signed tax bills cutting income taxes, capital gains taxes, dividend taxes, and estate taxes. It resulted in modest economic growth, but still below historical averages. Federal revenue plunged initially and recovered only with the Fed-induced housing market bubble.

Between 2000 and 2008, the debt-to-GDP ratio grew from 34 to 39 percent. According to CBO and Treasury Department studies, the predicted revenue boost due to economic growth never materialized.

In Bush’s first year, the federal government ran a $128 billion budget surplus, thanks in large part to the “peace dividend” that allowed the government to significantly slash military spending. But in his last year in office, the deficit was $458.6 billion, 3.1 percent of GDP.

In 2016, Trump signed his tax bill into law, dropping the corporate rate from 35 to 21 percent and lowering individual income tax rates for most brackets. Even with a short-term boost to GDP, federal revenues still fell $430 billion short of expectations in 2018-2019. Meanwhile, budget deficits were widening even before the pandemic. The Trump administration was on pace for a $1 trillion deficit even before COVID-19 reared its ugly head. We hadn’t seen deficits that big since the Great Recession.

Tax cuts implemented in 1964 during the Kennedy presidency offer a ray of hope. Federal revenue as a percentage of GDP remained stable. However, the economic landscape was significantly different then, and in the last 50 years, tax cuts initially tanked federal revenue, and partial recoveries in later years did not boost government receipts to pre-tax levels.

One could argue that the failure of the Trump tax cuts to boost growth was due to the pandemic. But this reveals a weakness in government forecasting. The CBO and other organizations that make projections typically start with unreasonable assumptions. For instance, the CBO report card on the Big Beautiful Bill assumes no major recession in the next decade. These Goldilocks scenarios seldom play out in reality.

It’s the Spending

The bottom line is we can’t depend on tax cuts and economic growth to solve the national debt problem. Even when revenues increase, spending has historically increased faster. Uncle Sam doesn’t have a revenue problem. It has a spending problem. Tax cuts alone can’t fix it.

In other words, it is going to take substantial cuts to spending. There doesn’t seem to be much political will for that.

Instead of aggressively tackling the borrowing and spending problem, Republicans seem content to trim around the edges and offer implausible assurances that mystical economic growth will take care of the rest.

If history is any indication – it won’t.

Mike Maharrey is a journalist and market analyst for Money Metals with over a decade of experience in precious metals. He holds a BS in accounting from the University of Kentucky and a BA in journalism from the University of South Florida.