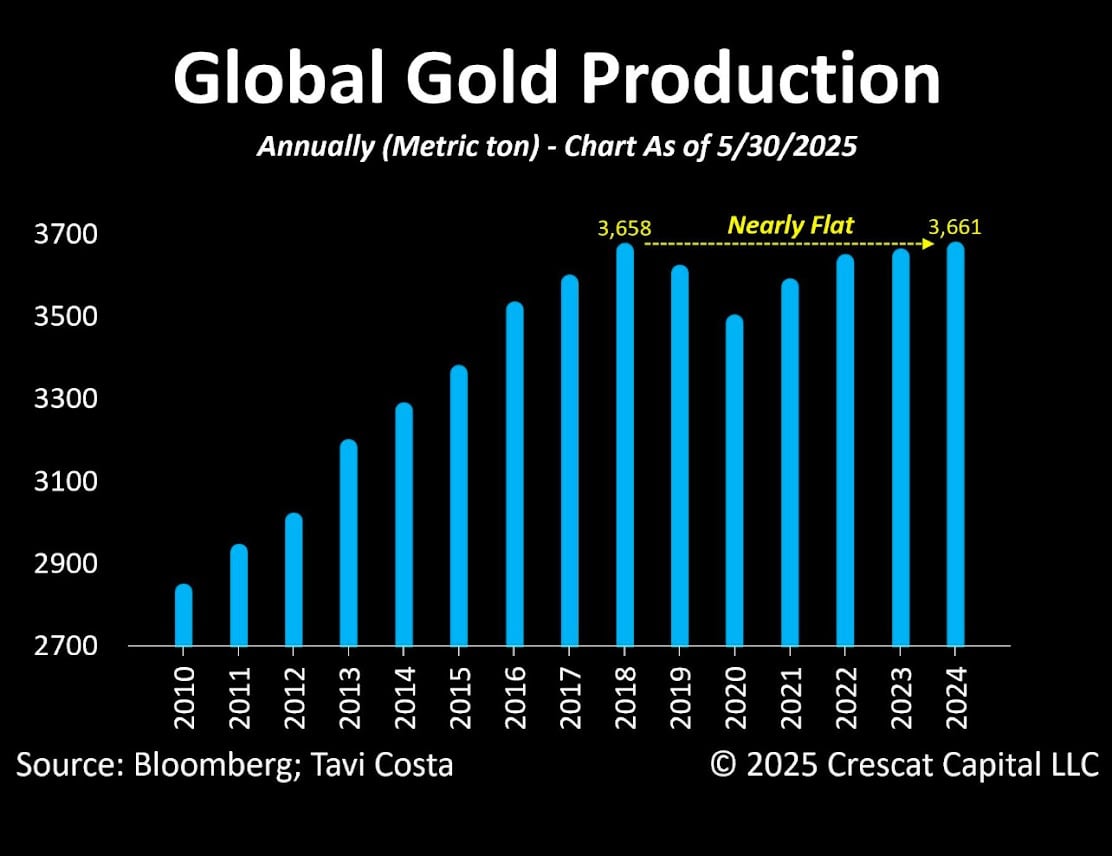

(Mike Maharrey, Money Metals News Service) Gold mine output has been basically flat since 2018. Could this signal that we are at or near “peak gold?”

Gold mines globally produced an estimated 3,661 tonnes of gold in 2024. It was a new record, but only 3 tonnes higher than the previous record set in 2018.

After slowing for several years, gold mine output fell by 1 percent in 2019. Although that year marked the first absolute decline in gold production since 2008, it continued a general trend of diminishing mine output.

Up until 2019, mine production had generally increased every year since the 1970s. There was a drop in production in 2008, but it was something of an anomaly, as it occurred at the onset of the 2008 financial crisis.

The return to 2018 mine output levels is encouraging. However, it’s too early to say that we have returned to an era of increasing mine output, and some industry insiders believe the plateau in recent years signals that we’re close to peak gold.

Peak Gold?

Peak gold is the point at which the amount of gold dug from the earth begins to shrink every year.

When the World Gold Council released its Gold Demand Trend report for 2022, it cautioned, “This lack of production growth gives further credence to claims that gold production is close to plateauing.”

Other players in the mining sector have raised concerns about the prospect of peak gold over the last several years.

Way back in 2016, Mining.com analyzed the data and concluded that there are no more easy gold discoveries.

That same year, MarketWatch asserted that we’re heading for “an impending gold production cliff” based on analysis by Sprott Asset Management. At the time, analysts said gold discoveries peaked in 2007, and a production peak would soon follow.

In 2017, World Gold Council Chairman Randall Oliphant cautioned that there are signs we’re reaching peak gold. He said in the near term, production is likely to plateau at best, before slowly declining as demand rises.

“We’re not going to fall off a cliff in the near term, but at the same time, it’s really hard to see how we’re going to produce enough gold to meet all this demand.”

At the same conference, Franco-Nevada Corp. CEO David Harquail said the gold mining industry was in an “ex-growth phase” where new mining projects are simply replacing older assets that are running out of ore.

In 2018, Goldcorp Chairman Ian Telfer said, “We’re right at peak gold here. … I don’t think there are any more mines out there, or nothing significant. And the exploration records indicate that.”

The following year, Deutsche Welle published an article headlined, “Is the World Running Out of Gold,” making the case for peak gold. The report highlighted the shrinking number of new deposit discoveries and declining ore grades.

“The largest and most prolific reserves have already been found,” Matthew Miller, an analyst at CFRA Research, told DW. “Gold miners are struggling to grow reserves in line with their production.”

According to a report According to a report by S&P Global analyst Paul Manalo released last fall, there have only been five major gold discoveries since 2020, totaling 17 million ounces of gold.

“The lack of quality discoveries in the recent decade does not bode well for the gold supply.”

South Africa provides something of a case study in peak gold. The country was once the world’s leading gold producer. In 2020, it dropped out of the top 10.

In December 2017, a study came out saying South Africa could run out of gold within four decades. Analysts said that at current production levels, the country only had 39 years of accessible gold reserves remaining.

There is cause for optimism. Technology advances could help mining companies identify new deposits and reach the more difficult-to-mine gold. The rising gold price could also boost exploration activity, leading to new discoveries.

However, Manalo projected that the gold supply would peak in 2026. He called the future trajectory of gold supply “a mixed bag.”

“The focus on old and existing assets has taken a toll on the number and size of discoveries in recent years, as proven by the lack of substantial discoveries in the last decade. However, the increasing gold budgets since 2017 bring a tad of optimism for the future of gold supply, as the number of initial resource announcements continue to grow in size and number.”

Whether we have reached peak gold or not remains debatable, but it’s clear that production has plateaued at least in the short term. Reversing the trend will require a significant industry focus on finding new deposits or developing methods to extract difficult-to-reach ore from the ground in a cost-effective manner.

Mike Maharrey is a journalist and market analyst for Money Metals with over a decade of experience in precious metals. He holds a BS in accounting from the University of Kentucky and a BA in journalism from the University of South Florida.