(Jon Miltimore, FEE) When Georgia resident Anita Jefferson pulls her Tesla out of her garage each morning, she knows it’s fully charged and ready to go. But she told a local reporter her confidence disappears when she hits the interstate. Charging stations seem few and far between, even at places where you’d expect them to be, like rest stops.

“The one place you would want to travel and stop would be a state rest stop,” Jefferson told an Atlanta news station. “I want to get an answer as to why they’re not there.”

Jefferson got her answer from WXIA-TV Atlanta’s Verify team: There are no charging stations at rest stops because they are prohibited under a federal law—one that stretches all the way back to the Eisenhower administration.

‘You Would Be Paying for That Energy’

In 1956, Ike signed into law a bill—the Federal-Aid Highway Act—that paved the way (pun intended) for the interstate highway system, which included rest areas at convenient locations.

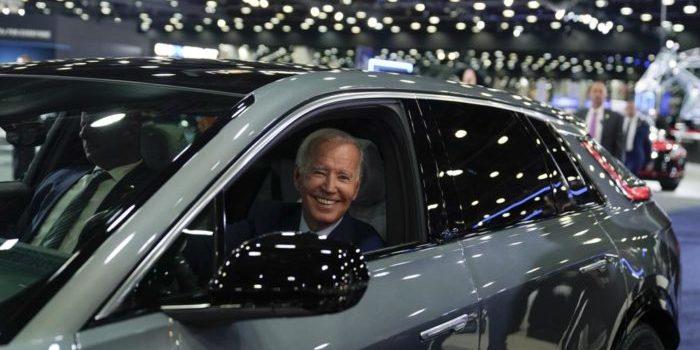

While there were numerous problems with the legislation, a relatively minor one was that it created strict limits on what could be sold at these rest stops. Today, federal law limits commercial sales to only a few items (including lottery tickets), the Verify team found. When President Joe Biden rolled out a $5 billion funding plan for states to create EV charging stations, he neglected to carve out a commercial exemption for EVs.

“You would be paying for that energy,” Natalie Dale of the Georgia Department of Transportation told WXIA-TV Atlanta. “That would count as commercialized use of the right-of-way and therefore not allowed under current federal regulations.”

Bureaucrats and Nonbureaucrats

If you think this sounds like an inauspicious roll out to the massive federal EV program, you’re not wrong.

Allowing drivers to charge their EVs at convenient, familiar locations that already exist along interstate highways is a no-brainer—yet this simple idea eluded lawmakers in Washington, DC.

Unfortunately, it illustrates a much larger problem with the top-down blueprint central planners are using to create their EV charging station network.

“We have approved plans for all 50 States, Puerto Rico and the District of Columbia to help ensure that Americans in every part of the country…can be positioned to unlock the savings and benefits of electric vehicles,” Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg said in a 2022 statement.

While it’s good the DOT isn’t trying to single-handedly map out the locations of thousands of EV charging stations across the country, there’s little reason to believe that state bureaucrats will be much more efficient. A review of state plans reveals a labyrinth of rules, regulations and stakeholders dictating everything from the maximum distance of EV stations from highways and interstates to the types of charging equipment stations can use to the types of power capabilities charging stations must have.

The primary reason drivers enjoy the great convenience of gasoline stations across the country—there are some 145,000 of them today—is that they rely on market forces, not central planning. Each year hundreds of new filling stations are created, not because a bureaucrat identified the right location but because an entrepreneur saw an opportunity for profit.

Bureaucracy will never be able to match the efficiency of markets, which use millions of signals to reach decisions, and are constantly being corrected by market changes, all in the pursuit of serving customers and making a profit.

This, the economist Ludwig von Mises pointed out, is precisely the opposite of what bureaucrats do.

“A bureaucrat differs from a nonbureaucrat precisely because he is working in a field in which it is impossible to appraise the result of a man’s effort in terms of money,” Mises wrote in his seminal work Bureaucracy.

Incentives and Knowledge

Just how burdensome these regulations will prove remains to be seen.

While some states will develop EV charging plans more amenable to market forces than others, all of them are likely to suffer to some extent because the push toward EVs itself has been top-down, driven by politicians trying to push consumers off of gas-powered vehicles.

What’s clear is that the bureaucratic structure of DOT’s charging station blueprint does not bode well for consumers. Charging technology and transportation are constantly evolving, and politicians and bureaucrats simply can’t respond to these changes as efficiently as markets.

So while there is much talk today that EV charging stations will soon outnumber gas stations, there’s reason to be skeptical of this claim—even with the government’s $5 billion spending spree.

There’s little reason to believe that state planners will create a framework with the proper incentive structure to meet the market’s needs. Bureaucrats and politicians lack both the knowledge and proper incentives to create a functional EV market.

If you doubt this, just ask Anita Jefferson, who can’t even charge her Tesla at rest stops—because of a federal law passed in 1956.